‘This year we see yet another rise in global fossil CO2 emissions, when we need a rapid decline.’

By Brendan Montague, The Ecologist (Creative Commons 4.0)

Global carbon emissions in 2022 remain at record levels – with no sign of the decrease that is urgently needed to limit warming to 1.5°C, according to the Global Carbon Project science team.

If current emissions levels persist, there is now a 50% chance that global warming of 1.5°C will be exceeded in nine years.

The new report projects total global CO2 emissions of 40.6 billion tonnes (GtCO2) in 2022. This is fuelled by fossil CO2 emissions which are projected to rise 1.0% compared to 2021, reaching 36.6 GtCO2 – slightly above the 2019 pre-COVID-19 levels. Emissions from land-use change, such as deforestation, are projected to be 3.9 GtCO2 in 2022.

Atmospheric

Projected emissions from coal and oil are above their 2021 levels, with oil being the largest contributor to total emissions growth. The growth in oil emissions can be largely explained by the delayed rebound of international aviation following COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

The 2022 picture among major emitters is mixed: emissions are projected to fall in China (0.9%) and the EU (0.8%), and increase in the USA (1.5%) and India (6%), with a 1.7% rise in the rest of the world combined.

The remaining carbon budget for a 50% likelihood to limit global warming to 1.5°C has reduced to 380 GtCO2 (exceeded after nine years if emissions remain at 2022 levels) and 1230 GtCO2 to limit to 2°C (30 years at 2022 emissions levels).

To reach zero CO2 emissions by 2050 would now require a decrease of about 1.4 GtCO2 each year, comparable to the observed fall in 2020 emissions resulting from COVID-19 lockdowns, highlighting the scale of the action required.

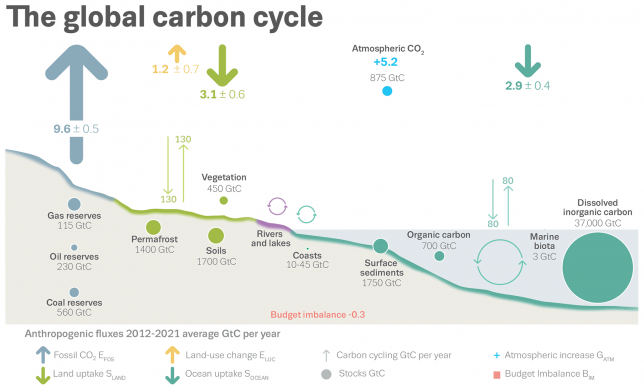

Land and ocean, which absorb and store carbon, continue to take up around half of the CO2 emissions. The ocean and land CO2 sinks are still increasing in response to the atmospheric CO2 increase, although climate change reduced this growth by an estimated 4% (ocean sink) and 17% (land sink) over the 2012-2021 decade.

Meaningful

This year’s carbon budget shows that the long-term rate of increasing fossil emissions has slowed. The average rise peaked at +3% per year during the 2000s, while growth in the last decade has been about +0.5% per year.

The research team – including the University of Exeter, the University of East Anglia (UEA), CICERO and Ludwig-Maximilian-University Munich – welcomed this slow-down, but said it was “far from the emissions decrease we need”.

The findings come as world leaders meet at COP27 in Egypt to discuss the climate crisis.

“This year we see yet another rise in global fossil CO2 emissions, when we need a rapid decline,” said Professor Pierre Friedlingstein, of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute, who led the study.

We are at a turning point and must not allow world events to distract us from the urgent and sustained need to cut our emissions.

—Professor Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society Research Professor at UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences

“There are some positive signs, but leaders meeting at COP27 will have to take meaningful action if we are to have any chance of limiting global warming close to 1.5°C. The Global Carbon Budget numbers monitor the progress on climate action and right now we are not seeing the action required.”

Emissions

Professor Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society Research Professor at UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences, said: “Our findings reveal turbulence in emissions patterns this year resulting from the pandemic and global energy crises.

“If governments respond by turbocharging clean energy investments and planting, not cutting, trees, global emissions could rapidly start to fall.

“We are at a turning point and must not allow world events to distract us from the urgent and sustained need to cut our emissions to stabilise the global climate and reduce cascading risks.”

Land-use changes, especially deforestation, are a significant source of CO2 emissions (about a tenth of the amount from fossil emissions). Indonesia, Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo contribute 58% of global land-use change emissions.

Transparent

Carbon removal via reforestation or new forests counterbalances half of the deforestation emissions, and the researchers say that stopping deforestation and increasing efforts to restore and expand forests constitutes a large opportunity to reduce emissions and increase removals in forests.

The Global Carbon Budget report projects that atmospheric CO2 concentrations will reach an average of 417.2 parts per million in 2022, more than 50% above pre-industrial levels.

The projection of 40.6 GtCO2 total emissions in 2022 is close to the 40.9 GtCO2 in 2019, which is the highest annual total ever.

The Global Carbon Budget report, produced by an international team of more than 100 scientists, examines both carbon sources and sinks. It provides an annual, peer-reviewed update, building on established methodologies in a fully transparent manner.