The cover page of the “Directors’ Duties Regarding Climate Change in Japan: 2025” report by Dr. Yoshihiro Yamada, Dr. Janis Sarra, and Dr. Masafumi Nakahigashi, published by the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI). The image of Mount Fuji symbolizes Japan’s resilience amidst the challenges of climate change.

Why Climate Change Matters

Climate change is a global challenge that’s affecting every corner of the world. Rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and unpredictable climate patterns are causing disruption, and no country is immune from its effects. Japan, an island nation, is particularly vulnerable to climate change because of its geographical location and dense population. Companies in Japan are now facing significant risks, not only from the physical impacts of climate change but also from the legal and financial responsibilities that come with it.

As climate change accelerates, the risks to businesses are no longer something that can be ignored or delayed. Corporate leaders in Japan are beginning to understand that failing to take action on climate-related risks could lead to severe consequences.

What Are the Risks of Climate Change?

Climate change poses two major types of risks to businesses: physical and transition risks.

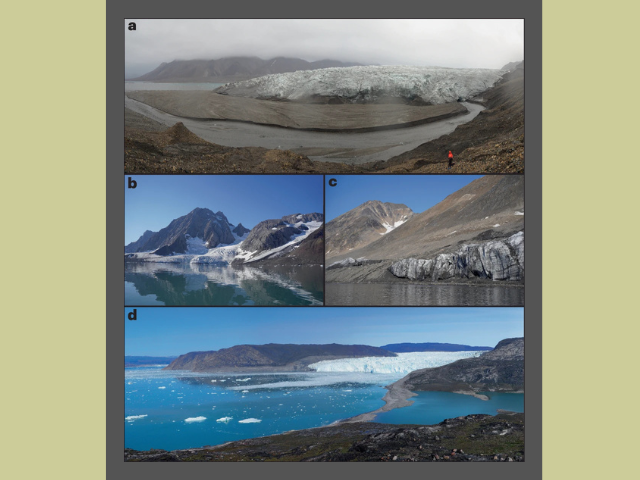

Physical Risks are those that arise from the direct impact of climate change. These risks are divided into two categories:

- Acute (immediate) risks: These are extreme events such as typhoons, floods, and heatwaves. For example, in recent years, Japan has experienced severe typhoons and record-breaking heatwaves, causing massive destruction.

- Chronic (long-term) risks: These refer to gradual changes such as rising sea levels and ongoing temperature increases. Both of which can have a slower but equally harmful impact on businesses, especially those relying on natural resources.

Transition Risks are related to the global shift toward a more sustainable, low-carbon economy. As governments, investors, and consumers push for greener practices, businesses face new challenges:

- Regulatory risks: New laws and policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions could impact how companies operate.

- Market risks: As consumers demand greener products, companies that do not adapt may lose market share.

- Technological risks: Companies that fail to innovate and adopt clean technologies might fall behind their competitors.

Why Japanese Companies Are Concerned About Climate Change

Japan faces multiple concerns when it comes to climate change. These concerns are not just about the physical damage caused by storms and rising seas—they also include financial and legal risks that could severely affect businesses.

Physical Risks: Japan is especially vulnerable to climate events like typhoons, heatwaves, and rising sea levels. For example, over the past decade, Japan has faced over JPY 13.7 trillion (USD $90.8 billion) in climate-related damages. Coastal cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya are at high risk of flooding. The country’s agricultural sector is struggling with changes in temperature and rainfall patterns.

Transition Risks: The global shift towards sustainability presents challenges for Japanese businesses. Companies that fail to reduce their carbon footprint or invest in cleaner technologies may lose out to more forward-thinking competitors. Additionally, businesses face the risk of stranded assets—where investments in fossil fuel infrastructure become worthless as the world moves toward renewable energy.

Legal and Financial Liability: Directors of Japanese companies have a legal responsibility to ensure that climate risks are managed properly. If they fail to take action, they could be held personally liable. Japanese laws now require businesses to disclose material climate risks, and failure to do so could lead to lawsuits for breach of fiduciary duty. The pressure is mounting for directors to act, as investors and regulators increasingly demand transparency on climate-related risks.

Investor Pressure: Institutional investors are increasingly focused on sustainability. In Japan, investors representing trillions of dollars are demanding that companies disclose their climate-related risks and take meaningful action. If a company fails to do so, it risks losing investor confidence, which could lead to higher costs of capital and reduced access to funding.

Systemic Risk to the Economy: The Bank of Japan has warned that failing to address climate risks could destabilize the financial system. Mismanagement of these risks could lead to falling asset prices, loss of economic stability, and even disruptions in Japan’s banking system.

How Climate Change Affects Japanese Companies

The effects of climate change are already being felt across many industries in Japan. For instance, the manufacturing sector is vulnerable to extreme weather events that damage facilities and disrupt supply chains. Similarly, Japan’s agricultural sector faces challenges like reduced rice yields due to rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall patterns.

The economic costs of not addressing these risks are significant. Companies that fail to prepare for climate change may suffer from damaged infrastructure, lost productivity, and increased operational costs. In some cases, the financial impact can be devastating, leading to significant losses in revenue and long-term damage to a company’s bottom line.

Legal Responsibilities for Directors in Japan

Corporate directors in Japan have a legal duty to manage the risks their companies face, including climate-related risks. According to Japanese corporate law, directors must act in the best interests of the company and ensure the company complies with all applicable laws and regulations. This includes climate-related risks.

Under Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, directors are required to oversee the company’s efforts to identify, assess, and manage climate risks. Failure to do so could result in personal liability. In particular, if a director neglects to integrate climate change into their governance strategy, they could face lawsuits from shareholders or be found in breach of their fiduciary duties.

The Role of Climate Governance in Business Success

Proper climate governance is crucial for businesses to remain competitive in a world that is increasingly focused on sustainability. Companies that integrate climate risks into their strategy are better positioned to succeed in the long term. Effective climate governance allows businesses to anticipate regulatory changes, innovate with cleaner technologies, and align with consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products.

In the long run, companies that take climate action seriously can build resilience, improve their reputation, and reduce risks associated with physical and transition challenges. On the other hand, companies that ignore climate risks may find themselves falling behind their competitors or even facing financial ruin.

The Growing Importance of Sustainability

As global investors push for more sustainable business practices, companies that fail to disclose their climate risks or take action to address them are likely to see a loss of investor confidence. Investors are increasingly looking for companies that are committed to reducing their carbon footprint and addressing climate-related risks in their business strategies.

Failure to meet these expectations could not only damage a company’s reputation but also increase the cost of capital and make it more difficult to attract investment in the future. Companies that adopt sustainability practices now will likely enjoy a competitive advantage in attracting responsible investors and staying ahead of regulatory trends.

What Should Directors Do?

Directors of Japanese companies must act now to integrate climate risk management into their governance structures. They should:

- Assess and disclose climate risks transparently.

- Seek expert advice to ensure they are making informed decisions about climate change.

- Ensure that the company’s strategy includes clear goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate impacts.

By taking these steps, directors can help safeguard their companies from the financial and legal risks associated with climate change and position them for long-term success in a decarbonized economy.

Call to Action

Japan is taking significant steps to address climate change, with its corporate sector increasingly aware of the legal and financial risks posed by climate impacts. As one of the countries leading the way in climate governance, Japan is setting a strong example for others to follow. However, the fight against climate change requires a global effort. The United States and other countries must step up their efforts to integrate climate risk into corporate governance, adopt stricter environmental regulations, and encourage businesses to embrace sustainability.

As individuals, we can support companies and governments that are prioritizing climate action. We can demand greater transparency and accountability from businesses on their climate-related actions and encourage them to follow Japan’s lead in addressing climate risks head-on. We need to act now—climate change is a challenge that requires bold leadership across the globe. Let’s work together to make sure that countries, especially those with significant global influence, do not fall behind in this critical fight for our planet’s future.

Yamada, Y., Sarra, J., & Nakahigashi, M. (2025). Directors’ Duties Regarding Climate Change in Japan: 2025. Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative.