Exposure to fracking and its effects is “a major public health concern,” said a study co-author.

By Kenny Stancil, Common Dreams (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

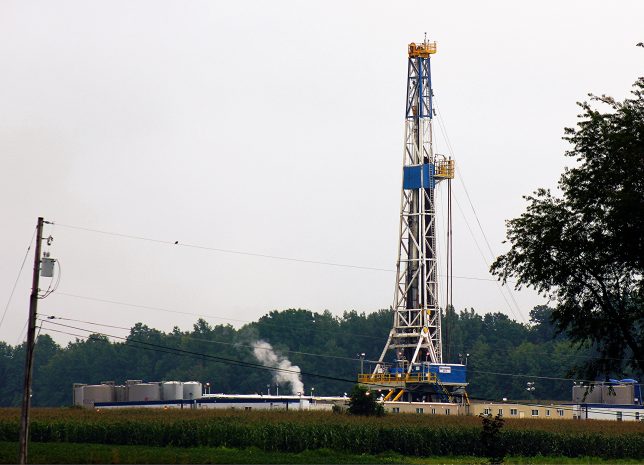

Adding further evidence of the negative public health impacts associated with planet-heating fossil fuel pollution, new research published Wednesday found that children living in close proximity to fracking and other so-called “unconventional” drilling operations at birth face significantly higher chances of developing childhood leukemia than those not residing near such activity.

Existing setback distances, which may be as little as 150 feet, are insufficiently protective of children’s health.

—Cassandra Clark, Postdoctoral Associate, Yale Cancer Center

The peer-reviewed study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives, examined the relationship between residential proximity to unconventional oil and gas development (UOGD) and risk of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common form of childhood leukemia.

Researchers compared 405 children ages 2 to 7 who were diagnosed with ALL in Pennsylvania between 2009 and 2017 to a control group of 2,080 children without leukemia matched on birth year. They measured the connection between in utero exposure to unconventional oil and gas activity and childhood leukemia diagnoses in two exposure windows: a “primary window” of three months pre-conception to one year prior to diagnosis and a “perinatal window” of pre-conception to birth.

Children with at least one fracking well within 2 kilometers (1.24 miles) of their birth residence during the primary window had 1.98 times the odds of developing ALL compared with those whose neighborhoods were free from such fossil fuel infrastructure, they found. Children who lived within 2 kilometers of at least one fracking well during the perinatal window were 2.8 times more likely to develop ALL compared with their unexposed counterparts.

Accounting for maternal race and socio-economic status reduced the strength of these relationships, but only slightly, with the adjusted odds of developing childhood leukemia 1.74 and 2.35 times higher for those exposed to UOGD during the primary and perinatal windows, respectively.

“Unconventional oil and gas development can both use and release chemicals that have been linked to cancer,” study co-author Nicole Deziel, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health, said in a statement.

Last summer, Physicians for Social Responsibility uncovered internal records revealing that since 2012, fossil fuel corporations have injected potentially carcinogenic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), or chemicals that can degrade into PFAS, into the ground while fracking for oil and gas—after former President Barack Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency approved their use despite agency scientists’ concerns about toxicity.

The possibility that children living in close proximity to such sites are “exposed to these chemical carcinogens is a major public health concern,” said Deziel.

Roughly 17.3 million people in the United States, including nearly four million children, live within a half-mile radius of active oil and gas production, according to the Oil & Gas Threat Map, a geospatial analysis released in May.

Not only do those people have a greater risk of suffering severe health problems from toxic air pollution, but as the research published Wednesday notes, fracking also contaminates drinking water—creating another pathway of exposure to cancer-linked chemicals.

The new study adds to a growing body of literature documenting the deleterious health and environmental consequences of fracking and other forms of fossil fuel extraction.

Research published earlier this year found that residential proximity to UOGD is correlated with a higher risk of dying early. More broadly, the World Health Organization warned last year that burning coal, oil, and gas is “causing millions of premature deaths every year through air pollutants, costing the global economy billions of dollars annually, and fueling the climate crisis.”

Other recent studies have estimated that slashing energy-related air pollution would prevent more than 50,000 premature deaths and save $608 billion per year in the U.S. alone, while eliminating greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 would save 74 million lives around the globe this century—demonstrating that the “mortality cost of carbon” is astronomical.

“Fracking threatens every person on the planet, directly or indirectly. It should be banned entirely.

—Wenonah Hauter, Executive Director, Food & Water Watch

Despite this obvious case for rapid decarbonization, President Joe Biden has yet to use his executive authority to cancel nearly two dozen fracked gas export projects that are set to unleash pollution equivalent to roughly 400 new coal-fired power plants.

The researchers behind the paper published Wednesday hope that their findings will be used to improve public policy, including better regulation of “setback distances”—the required minimum distance between a private residence or other sensitive location and fracking wells.

Setback distances are currently being debated across the U.S., with some communities calling for setback distances to be lengthened to more than 305 meters (1,000 feet) or as far as 1,000 meters (3,281 feet), the authors wrote.

In Pennsylvania, where the study was based, the current setback distance is 152 meters (499 feet), up from 61 meters (200 feet) in 2012. Researchers, meanwhile, observed elevated risks of childhood leukemia from fracking activity within a 2,000 meter (6,562 feet) radius.

“Existing setback distances, which may be as little as 150 feet, are insufficiently protective of children’s health,” lead author Cassandra Clark, a postdoctoral associate at the Yale Cancer Center, said in a statement. “We hope that studies like ours are taken into account in the ongoing policy discussion around UOG setback distances.”

Other critics of fracking have demanded far more extensive federal action, including prohibiting the practice entirely.

As “hundreds of scientific studies and thousands of pages of data have already shown over the last decade,” Food & Water Watch executive director Wenonah Hauter said last year, “fracking is inherently hazardous to the health and safety of people and communities in proximity to it.”

“This says nothing of the dreadful impact fossil fuel extraction and burning is having on our runaway climate crisis,” she added. “Fracking threatens every person on the planet, directly or indirectly. It should be banned entirely.”