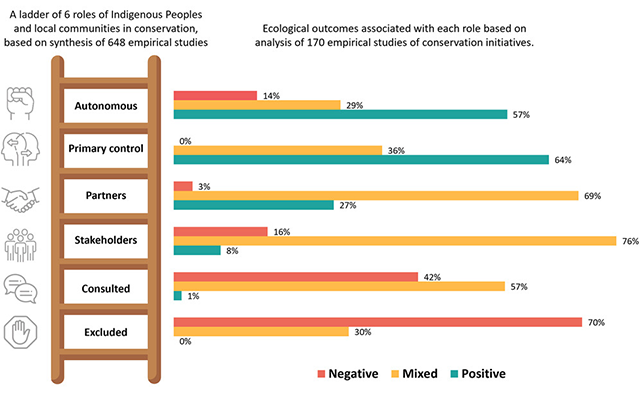

A social outcomes ladder of 6 types of roles of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in conservation governance, based on synthesis of 648 empirical studies.

As global biodiversity continues to face threats from various fronts, the role of Indigenous peoples (IPs) and local communities (LCs) has never been more crucial. A recent study published in One Earth underscores the need for an equitable governance approach that recognizes and empowers these groups, offering sustainable and effective solutions to conservation challenges. Let’s look at transformative roles that IPs and LCs can play in biodiversity conservation, in alignment with the Global Biodiversity Framework targets.

Understanding the Global Biodiversity Framework

The Global Biodiversity Framework, established during the Kunming-Montreal conference, sets ambitious targets to safeguard the planet’s biological resources. A key target within this framework is the conservation of 30% of land and sea areas by 2030 through equitably governed systems. This goal emphasizes the importance of recognizing diverse values, ensuring rights to ancestral territories, upholding cultural practices, and involving all relevant actors in decision-making processes to achieve effective conservation outcomes.

Empirical Evidence and Ecological Outcomes

A comprehensive review of 648 empirical studies reveals that conservation initiatives where IPs and LCs have equal partnership or primary control lead to more positive ecological outcomes. This evidence strongly supports a governance model that respects and integrates the knowledge systems and customary practices of IPs and LCs, enhancing biodiversity conservation’s effectiveness and sustainability.

The Changing Paradigm of Conservation Governance

Traditional conservation methods often overlooked the intrinsic value and knowledge of IPs and LCs, limiting their roles to mere participants. However, a shift towards equitable governance is gaining momentum, where these communities are not only participants but leaders with significant control and recognition of their traditional values and institutions. This approach is proving essential for the ecological success of conservation efforts.

Roles of IPs and LCs in Governance

The typology of roles that IPs and LCs can assume in conservation governance ranges from excluded to autonomous.

The typology structure includes six distinct roles that reflect varying levels of participation, influence, and control:

- Excluded: IPs and LCs have no participation or benefits.

- Consultees: Minimal influence despite receiving some information or benefits.

- Stakeholders: Some ability to influence decisions but limited control.

- Partners: Equal partners or co-managers, sharing power in conservation efforts.

- Primary Control: Primary authority with respected leadership and rights, though not fully autonomous.

- Autonomous: Full autonomy with their knowledge and institutions fully recognized.

Each role on this spectrum provides insights into how different levels of involvement and control impact conservation outcomes. The findings advocate for policies that elevate IPs and LCs from mere stakeholders to leaders, recognizing their capability to manage and conserve natural resources effectively.

Overview of Intervention Types in Conservation Initiatives

Theories about involvement in conservation management suggest that decision-making is a complex process that includes many participants from different levels, all with their own interests and levels of power. The types of interventions identified in the reviewed cases include:

- Protected and Conserved Areas (67.9%): Most common, focusing on designated areas for biodiversity preservation.

- Livelihood Projects or Tourism Ventures (56.9%): Projects supporting sustainable livelihoods or integrating conservation with tourism.

- Species Protection or Sustainable Use Regulations (53.9%): Efforts focused on specific species protection or sustainable resource use.

- Local or Indigenous Stewardship (36.7%): Direct management or major influence by IPs and LCs in conservation efforts.

- Ecosystem Restoration (15.7%): Initiatives aimed at restoring ecosystems to their natural states.

- Incentives, Compensation, Revenue Sharing, or Market Instruments (13.6%): Economic tools to promote conservation.

- Education and Capacity Building (10.6%): Focus on educating IPs and LCs and building their capacity for conservation.

This complexity means we need to carefully analyze how much influence different participants have at various stages of the conservation efforts. Instead of using simple measures like how often IPs and LCs attend meetings or their personal views on conservation, we should look more deeply at how meaningful their participation is and how the conservation processes are governed. This detailed examination will help us better understand the true role of IPs and LCs in making conservation decisions.

Statistical Analysis and Policy Implications

Statistical analyses corroborate that higher degrees of control and participation by IPs and LCs correlate with favorable ecological and social outcomes. These outcomes not only emphasize the need for a policy shift towards more inclusive governance but also highlight the importance of IPs and LCs in achieving the targets set by the Global Biodiversity Framework. The study suggests that empowering IPs and LCs is not just beneficial but necessary for the long-term success of global biodiversity conservation.

Summing Up

The pivotal role of IPs and LCs in biodiversity conservation is clear. By transitioning to governance models that provide full recognition and control to these communities, conservation efforts can be significantly more effective and equitable. It’s time for conservation policies and practices to reflect this reality, ensuring that IPs and LCs are at the forefront of the decision-making processes, thus safeguarding biodiversity for future generations.

Source: Dawson, N. M., Coolsaet, B., Bhardwaj, A., Booker, F., Brown, D., Lliso, B., Loos, J., Martin, A., Oliva, M., Pascual, U., Sherpa, P., & Worsdell, T. (2024). Is it just conservation? A typology of Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ roles in conserving biodiversity. One Earth.