As storms grow more severe and temperatures climb, contamination of groundwater by animal and human waste could be on the rise as well.

By Kari Lydersen (@karilydersen1), writer, ensia (CC BY-ND 3.0).

Editor’s note: This story is part of a nine-month investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. View related stories here.

Many people assume that the water that flows from our taps is free of harmful microorganisms. But each year thousands of Americans in rural areas, small towns and even some cities are sickened by living pathogens that can flourish in untreated or inadequately treated water from private wells and municipal systems.

An increase in heavy precipitation with climate change means the risk of drinking water contamination by bacteria, viruses and other microbes could also increase, especially in places where reliance on groundwater, proximity to agricultural operations and certain types of geology increase vulnerability.

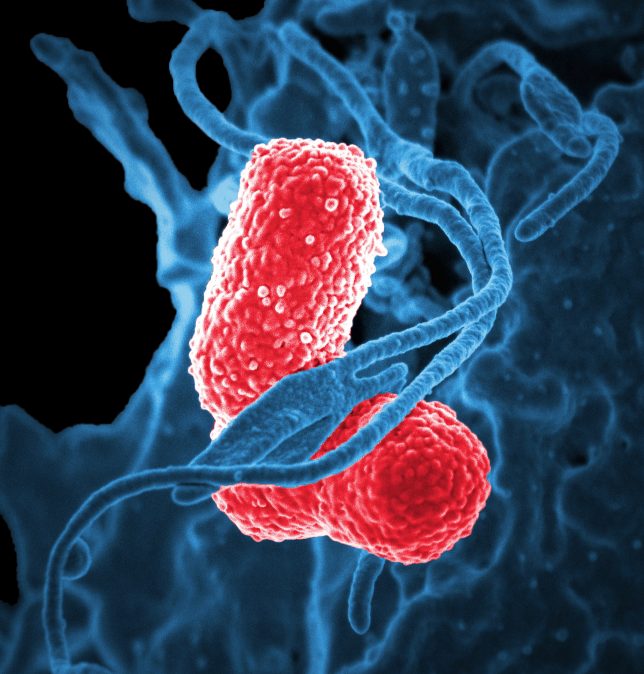

Bacteria like E. coli, Salmonella and Campylobacter, and viruses like hepatitis, norovirus and rotavirus, are all found in drinking water contaminated with human and animal fecal waste. These can cause gastrointestinal and other ailments. For some that’s a matter of discomfort, but for children, the elderly and those with compromised immune systems, this can be dangerous, debilitating and even deadly.

“We’ve known for years that extreme [weather] events can cause risk for waterborne outbreaks — in developing countries, but also in developed countries,” says epidemiologist Elsio Wunder Jr., an expert in water sanitation at the Yale School of Public Health.

Pathogens in U.S. public drinking water systems cause upwards of 4 million digestive tract illnesses each year. A 2017 study by Florida State University assistant professor of geography Christopher Uejio and colleagues predicted an increase in such illnesses in children under age 5 in relation to climate change, noting the impact on “small rural” municipalities that distribute untreated groundwater in their systems.

Multiple studies have documented the risk of precipitation-driven drinking water contamination in Wisconsin, a state especially susceptible because of its livestock operations and geology. A 2010 report by Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, associate professor of pediatrics Patrick Drayna and colleagues found that visits to a Wisconsin pediatric hospital for gastrointestinal symptoms increased an estimated 11% four days after rainfall.

Rainwater courses through lagoons of manure or manure spread on fields as fertilizer, picking up pathogens and carrying them into groundwater as it seeps down into the soil. The porous dolomite that underlies parts of Wisconsin and surrounding states allows pathogen-laden rainwater to make its way into the aquifers that feed wells and municipal water systems. Human fecal pathogens can also make their way from septic systems into drinking water supplies as rainwater permeates.

“Groundwater was rainfall, it just takes a while to get there,” explains Mark Borchardt, a microbiologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), who reported in 2019 that 60% of wells in northeastern Wisconsin’s Kewaunee County were contaminated with microbes found in fecal waste. “Rainfall has chemistries that detach microorganisms. When it touches a pathogen attached to a soil particle, the pathogen can be released and move on.”

In northern climates, frozen ground makes it less likely that pathogens can get into groundwater in winter. But warmer winters expected with climate change likely mean that ground will be frozen less of the time and that precipitation will fall as rain instead of snow, increasing the chances for pathogens to move.

Meanwhile drought — also expected to increase with climate change — can increase the risk of pathogen contamination as well.

“At the most basic level, drought can leave people without easy access to water, and they have to get water from a less-safe source,” says Jeni Miller, executive director of the Global Climate and Health Alliance. “And with less water in the aquifers, [pathogens] become more concentrated,” meaning someone could get a higher dose of pathogens from drinking water from aquifer-fed wells, and the pathogens may be more likely to cause illness when ingested.

Source Matters

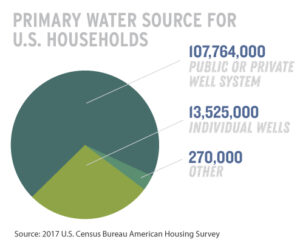

Private wells often pose the greatest risk of sickness from pathogen contamination, since there are typically no requirements for testing or treating wells, and it is usually up to an individual homeowner to discover or deal with contamination. More than 13 million households nationwide get their drinking water from such wells.

Well contamination has been a problem in not only the Midwest but in Appalachia and other regions as well, often in areas where residents lack the funds for testing or comprehensive maintenance. The organization Appalachian Voices in 2009 cited a USDA study, saying it found “over 50 percent of the private drinking water wells in the Appalachian area of Kentucky are contaminated with disease-carrying pathogens” because of poorly managed “straight” sewage pipes that contaminate surface water. A 2017 report by University of Tennessee registered nurse and then–doctoral student Erin Arcipowski and colleagues reported that pathogenic contamination of drinking water is a serious issue in low-income rural areas of Appalachia. The researchers noted that some residents lack funds for maintaining wells and might rely on “expensive bottled water from a remote convenience store” if they don’t have drinkable water at home. The study found E. coli or fecal coliform bacteria in 15 of 16 sites where water was used for drinking or recreation.

Municipal water systems that tap groundwater can also be at risk, since there are no federal mandates that groundwater be treated before distribution, according to Borchardt. About 95,000 such systems nationwide do not disinfect their water, and about 85,000 people in Wisconsin are served by systems that do not disinfect.

Federal law does require disinfection of drinking water drawn from surface sources, so there is seemingly less risk people will get sick from these systems. But treatment systems can malfunction when heavy rain makes the water more turbid (cloudy).

In 1993 the city of Milwaukee suffered an outbreak of Cryptosporidium, a tiny parasite, that sickened more than 400,000 people with diarrhea and killed 69. A water treatment plant had inadequately treated turbid water that may have been contaminated with the parasite by agricultural or human waste carried into Lake Michigan by rain and snow melt. Between 2009 and 2017, contaminated drinking water caused 339 cases of Cryptosporidium nationwide, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pipes can be a problem, too. If the distribution systems that deliver drinking water contain cracks, pathogen-laden rainwater or groundwater can infiltrate them. If pipes carrying sewage are nearby and are also leaking, rainwater can help move pathogens from sewage into drinking water.

“When pipes leak, they don’t just leak out, they also leak in,” Borchardt notes.

Groundwater was a suspected source of contamination by the “brain-eating” amoeba Naegleria fowleri in Louisiana in recent years, which is typically deadly if it enters the nose. If groundwater tapped for drinking water is not disinfected or if disinfection systems fail, Naegleria may be present in tap water. Naegleria-contaminated groundwater can also enter water systems when pipes break. There was also an outbreak in Texas this fall, and because Naegleria thrives in warm temperatures, it may become an increasing problem with climate change.

Reducing Risk

Governments and individuals can take a number of measures to reduce the risk of pathogens in drinking water. State or local governments can impose stricter controls on manure storage and spreading, including buffers and setbacks from residences.

“We currently have industrial-scale ranching and raising animals for meat and eggs, producing industrial-size pools of animal waste,” says Miller. “We need to reduce all those things that threaten our water supply as much as possible.”

Widespread testing can help identify contamination before people get sick. And municipalities that aren’t disinfecting their water can do so with UV light or other systems. Individuals can also install treatment systems for their own well water.

“More people are installing treatment systems in their homes, but systems are quite expensive, it could be several thousand dollars and requires regular maintenance which we people are not always very good at,” says Scott Laeser, water program director of the advocacy group Clean Wisconsin. “Ultimately we need to be focused on preventing pollution from contaminating our groundwater.”

Karen Levy, an associate professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington, has long studied waterborne disease. She said that while increased rains could mean more contamination risk in the U.S., it’s important people have faith in public drinking water systems, building the will to maintain and protect those systems, rather than turning to expensive and environmentally destructive bottled water.

“It’s really important to not scare people away from drinking water,” Levy said.

Meanwhile the risk of drinking water contamination is just one more reason, scientists agree, that people and governments must do all they can to curb climate change.

“All of the climate models show an increase in the frequency of extreme events, this means at both ends, more droughts and more floods,” says Jonathan Patz, director of the Global Health Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The bottom line is it should be a multi-pronged, multi-level approach where not only do we have to anticipate heavy rainfall events that are expected with climate change, but instead of building systems for what we’re used to now, our water systems need to be much stronger.”