Deforestation soars in Nigeria’s gorilla habitat: ‘We are running out of time’

by Orji Sunday, Mongabay (CC BY-ND 4.0).

- Afi River Forest Reserve (ARFR), in eastern Nigeria’s Cross River state, is an important habitat corridor that connects imperiled populations of critically endangered Cross River gorillas.

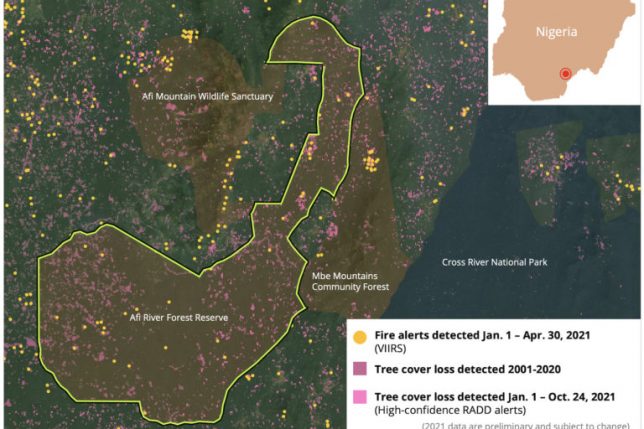

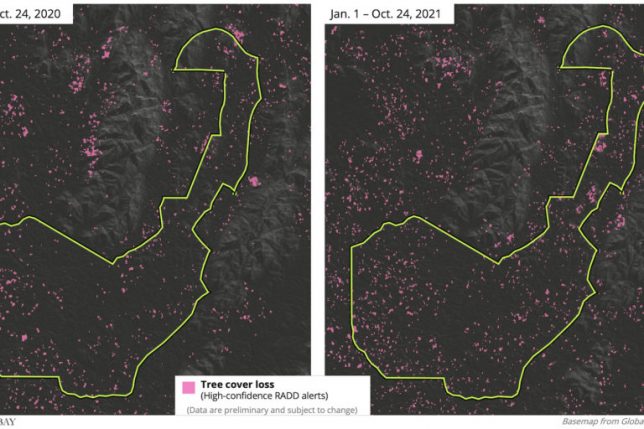

- But deforestation has been rising both in ARFR and elsewhere in Cross River; satellite data show 2020 was the biggest year for forest loss both in the state and in the reserve since around the turn of the century – and preliminary data for 2021 suggest this year is on track to exceed even 2020.

- Poverty-fueled illegal logging and farming is behind much of the deforestation in ARFR. Resource wars have broken out between communities that have claimed the lives of more than 100, local sources say.

- Authorities say a lack of financial support and threats of violence are limiting their ability to adequately protect what forest remains.

IKOM, Nigeria — When 57-year-old Linus Otu was a child, each dawn arrived with the chatter of monkeys and occasional belches of gorillas from the mountain that overlooks his small bungalow home in the village of Kanyang II in southeastern Nigeria’s Cross River state. He recalled peering up at the foggy, forested mountains, uncertain what to make of his noisy animal neighbors.

One morning, while exploring the banks of the Afi River, Otu came upon a mother chimpanzee bathing its infant. “It acted like a human, like a mother will care for her baby,” Otu told Mongabay.

But when Otu walks beside the river today, once a watering hole for diverse wildlife, the cacophony of the forest is different, quieter. Decades of habitat loss have taken their toll on Cross River’s rainforest, and even the state’s protected areas haven’t been able to escape the intertwined forces of agriculture, poverty and war.

Afi River Forest Reserve (ARFR), named after the river that bisects it into two unequal halves, was established in the 1930 to protect more than 300 square kilometers (about 116 square miles) of rainforest near Nigeria’s border with Cameroon. The reserve, now managed by the government’s Cross River State Forestry Commission harbors many species, including blue duikers (Philantomba monticola), bay duikers (Cephalophus dorsalis), red river hogs (Potamochoerus porcus), yellow-backed duikers (C. silvicultor), mona monkeys (Cercopithecus mona) and African brush-tailed porcupines (Atherurus africanus).

The region is also home to critically endangered Cross River gorillas (Gorilla gorilla diehli) that occasionally inhabit ARFR but prefer to live more permanently in nearby Cross River National Park and adjacent Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary (AMWS). However, despite becoming an official protected area in 2000, poaching has persisted in AMWS; according to Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), an infant gorilla was killed by a snare trap in 2010; in 2012, two gorilla carcasses were found at a hunter’s camp.

The Cross River gorilla remains Africa’s most endangered ape, with fewer than 300 individuals believed to remain in the wild, all of which are relegated to a small, mountainous portion along the Nigeria-Cameroon border. Around 100 – a third of the entire subspecies – are found in a patchwork of three adjoining protected areas in Nigeria: AMWS, the Mbe Mountains Community Sanctuary and the contiguous Okwangwo division of Cross River National Park.

Poaching isn’t the only threat that the gorillas face. Habitat loss is on the rise in Cross River, with satellite data from the University of Maryland (UMD) showing that more primary forest was cleared in 2020 than in any year prior since measurement began in 2002. Overall, Cross River state lost nearly 5% of its primary forest cover between 2002 and 2020.

As with many of Nigeria’s forest reserves, ARFR has been beset by increasing deforestation. The reserve has had the highest rate of forest loss in the region, according to a 2018 study published in the Open Journal of Forestry, which found that annual deforestation in ARFR increased twelve-fold between 1986 and 2010. UMD satellite data show the reserve lost another 4% of its primary forest cover between 2011 and 2020. Like Cross River state, 2020 saw ARFR’s highest levels of deforestation since the beginning of the century – and preliminary data suggest the reserve is experiencing another year of intense habitat loss.

Habitat in flames

2021 started with a bang in Cross River state as the region saw some of its highest fire activity in years, according to data from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The data show several fires spread and broke out in ARFR.

Local sources said the 2021 fire season was one of the worst they’ve ever experienced in the region, dwarfing even the outbreak of 2002. Blazes in ARFR lingered for several weeks, defying firefighting efforts from local communities, said George Mbang, a WCS ranger who works in adjacent Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuar. Mbang said he and his team were eventually able to snuff out the fires, but not before dozens of farms and tracts of forest were lost in and near the two protected areas.

Sources said the origins of the fires remain unclear but suspect that some of them may have been started by farmers clearing land for new fields. Satellite imagery shows many of the fires that invaded ARFR occurred near areas that had been previously cleared.

Fighting forest fires in ARFR is difficult. Rangers are challenged by a lack of resources and varied, inaccessible terrain, with peaks soaring to 1,300 meters above sea level. Mbang said unstable rocky outcrops can become dislodged as fire burns the vegetation holding them together and can crush firefighters and houses as they careen downhill. He said that the only option is to raze the edges of affected areas to restrict further spread.

Some communities around ARFR have proposed new, stiffer penalties for those linked to fire outbreaks, Otu told Mongabay. He said the new clause, when fully enshrined, will require those found responsible to forfeit their own cocoa farms to the victims of fire incidents, in addition to monetary fines.

Farmers told Mongabay that fires that spread onto land they already used for agriculture deplete nutrients in the soil, forcing them to seek – and clear – replacement farmland in protected areas. Research has shown that fire replenishes some, but not all, nutrients in the soil as it breaks down organic matter. Critically, fire has been found to reduce nitrogen in soil, and farmers told Mongabay that it was easier for them to clear more forest for new farmland than use fertilizer to replace nitrogen and other nutrients.

Poverty and conflict

During a visit to ARFR in Aug. 2021, Mongabay observed several trucks loading logged timber day and night in and near ARFR, destined for urban centers where a growing demand for timber products is increasing the pressure on dwindling habitat in Nigeria’s forest reserves. Many areas of ARFR were pockmarked by deforestation and strewn with logs as distant rattles of chainsaws mingled with the moist forest breeze.

Cocoa trees bearing yellow and green pods spread across the undulating landscape in and around the reserve. It was the peak of farming season, with farmers continuing to clear new farms even as rains fell, burning stumps and applying chemicals to control crop pests and disease. At numerous homesteads, farmers were collecting harvested cocoa pods and bagging dried beans. Bagged cocoa beans were then weighed and loaded onto trucks at depots, where they’ll be transported to nearby cities before being exported abroad.

The search for new agricultural land to grow cocoa, plantain, banana and cassava is driving forest loss in ARFR, said Otu, who is a former community leader of Kanyang II. “As you enter you start clearing as much as you have the power to clear,” he said. “Almost every portion of the reserve has been claimed.”

Cocoa farming became commercialized fairly recently in surrounding communities, spurring a new wave of demand for larger farming spaces. Farmers, backed by wealthy cocoa merchants from urban centers, competed to dominate the emerging market primarily by farming larger portions each year. The surge of cocoa farms in the likes of ARFR, linked to the growing demand for the product in the international market, has made Nigeria the world’s fourth largest cocoa producer.

With most surrounding communal forests nearly depleted, community residents say customary practice allows them to permanently own any portion of land they can clear and farm in ARFR – despite official laws that prohibit it. Several farmers told Mongabay that they have cleared more land in the reserve than they need in the short term, hoping to either transfer the land to their children, use it for new farms or rent it out to migrant cocoa farmers for a fee. In addition, locals said that by taking possession of large expanses of land, they stand a chance of receiving eviction payouts if the government steps in to reclaim remaining forest in the reserve.

The underlying factor driving deforestation in ARFR and elsewhere in the country is poverty. Nearly half of Nigeria’s 190 million people live in extreme poverty, and unemployment reached a record 33% in 2020, according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics. With few legal options to make a living and with the country’s population expected to double by 2050, Nigerians say they are forced to turn to the forests to make a living.

The situation has deteriorated to the point at which resource wars have broken out, local sources told Mongabay. Power conflicts and boundary disputes over access to timber, cropland, bushmeat and other forest products have intensified in recent years as resources diminish in and around ARFR and communities fight to control what remains.

Customary negotiators once relied on traditional boundaries such as trees, rivers and oral practices to delineate borders between local communities and mitigate disputes. But 61-year-old Leonard Akam said this is no longer sufficient to deter bloodshed, and multiple sources said that resource wars between communities have led to the deaths of at least 100 people.

Akam is calm in his demeanor, often witty with words and brutally honest. He was the head of the Boje clan when a dispute over communal boundaries within the reserve with neighboring clan Nsadop led to a brutal communal war in 2010. “So many lives were lost,” Akam told Mongabay. Local authorities temporarily restored peace by deploying the military, complete with a panel of inquiry and an arbitration committee. But Akam said the government’s approach was half-hearted and ineffective.

One such war erupted in 2018 between the Boje and Iso Bendeghe communities. After a year of conflict in which at least two people were reportedly killed, the Nigerian government again deployed the military in an effort to restore peace in the area.

This time intervention was more successful. A fragile truce was struck between Boje, Nsadop and Iso Bendeghe as well as other communities such as Bouanchor and Katabang. Boundary tracing, aided by old documents retrieved from the archive, is in progress. Meanwhile, communities around the reserve are in dialogue to avoid further bloodshed.

Despite this progress, Akam said sustainable peace depends on addressing the root causes of the crisis: unemployment, lack of infrastructure, poor educational systems – and the poverty that underpins them all.

Running out of time

ARFR has long been too degraded to provide permanent habitat for Cross River gorillas but researchers still consider it a lifeline that connects resident populations in AMWS and Cross River National Park. However, ARFR may be losing its capacity as a habitat corridor. A 2007 study published in Molecular Ecology found evidence of “low levels” of gene flow between gorilla populations, suggesting that while individuals were still able to move between populations to breed, it wasn’t happening very often. A related study published in 2008 in the American Journal of Primatology found Cross River gorillas have less genetic diversity than western gorillas (G. gorilla gorilla), putting them at greater risk of extinction.

“These results emphasize the need for maintaining connectivity in fragmented populations and highlight the importance of allowing small populations to expand,” the study states.

A 2008 survey of the southeastern portion of ARFR conducted by WCS in 2008 found that primary forest covered just 24% of the surveyed area.

“Unless the current rate of habitat destruction is reduced, the critical link between the AMWS and the Mbe Mountains that this reserve provides will be lost, with the obvious consequence being further isolation of the Afi gorillas and other wildlife,” WCS Cross River landscape program director Inaoyom Imong and primate researcher Kathy L. Wood wrote in their survey report. “Results of this survey show that farming, uncontrolled logging, and hunting are currently the most important threats to the Afi River Forest Reserve. These threats need to be urgently addressed in order to protect this very important corridor area.”

But in the years since this research was published, deforestation in ARFR has only increased. Satellite data from the University of Maryland show the reserve lost around 4% of its remaining primary forests between 2009 and 2020, with more deforestation detected in 2020 than in any year previous since measurement began in 2002. Preliminary tree cover loss data for 2021 and NASA fire data indicate ARFR is experiencing another year of heavy deforestation.

While recent conservation efforts led by the government, local communities and NGOs have focused on gorilla strongholds Afi Mountain Wildlife Reserve and Cross River National Park, habitat corridors like ARFR remain porous.

Some blame the government for allowing the destruction of ARFR to continue. A 2017 capacity study of the Cross River State Forestry Commission concluded that the agency is “grossly understaffed and deficient in managing the forest estate,” with only 324 active staff – less than 10% of the 3,458 recommended by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

Paddy Njar, director of wildlife at the Cross River State Forestry Commission said there’s little else they can do without better state support.

“There is no support from the state government,” Njar said. “We are seriously handicapped. No mobility. No funding. No allowances for rangers who ought to be on patrol. I feel bad.”

Njar said this lack of state support has emboldened loggers and communities to exploit protected forest. He told Mongabay the agency doesn’t even have access to permanent vehicles necessary for enforcement. He said he is in the process of requesting support from other institutions within and outside Nigeria to secure vehicles to carry out monitoring of protected sites and other field operations.

“If we have mobility, we can control 80% of the deforestation happening at the moment,” Njar said. “We have the laws but we are not mobile enough to reach the field for enforcement. For now, the commission has no single vehicle. Sometimes rangers have to hire motorcycles before they go to work.”

But Njar said that even when they’re able to get to the areas they’re supposed to protect, rangers are often still prevented from doing their job. He spoke of a recent operation in which his team arrested loggers and confiscated their chainsaws in one of the state’s protected areas. But he said their enforcement efforts were thwarted when the loggers joined forces with a nearby community to block the exit road and threatened to assault the rangers unless they surrendered the chainsaws.

“I can’t risk my life anymore,” Njar said.

Meanwhile, conservationists say the porosity of ARFR is bleeding threats into other nearby protected areas, including those that shelter critically endangered gorilla populations. For instance, WCS said its staff have documented more than 1,000 farms in adjacent Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary, as well as hundreds of snares, gun cartridges and empty shells, and chainsaws recovered from loggers.

“Now that they have almost finished Afi River Forest Reserve, their attention has turned to the sanctuary,” Mbang told Mongabay.

Imong sums up the situation with dire concision: “We are running out of time to save what is left of the forest.”

Editor’s note: This story was powered by Places to Watch, a Global Forest Watch (GFW) initiative designed to quickly identify concerning forest loss around the world and catalyze further investigation of these areas. Places to Watch draws on a combination of near-real-time satellite data, automated algorithms and field intelligence to identify new areas on a monthly basis. In partnership with Mongabay, GFW is supporting data-driven journalism by providing data and maps generated by Places to Watch. Mongabay maintains complete editorial independence over the stories reported using this data.