Federal, state and local governments all have a hand in protecting public water systems and private wells from contamination.

By Brett Walton, writer, ensia (CC BY-ND 3.0)

Originally published on September 29, 2020 — Editor’s note: This story is part of a nine-month investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. Read the launch story, “Thirsting for Solutions,” here.

Who’s responsible for making sure the water you drink is safe? Ultimately, you are. But if you live in the U.S., a variety of federal, state and local entities are involved as well.

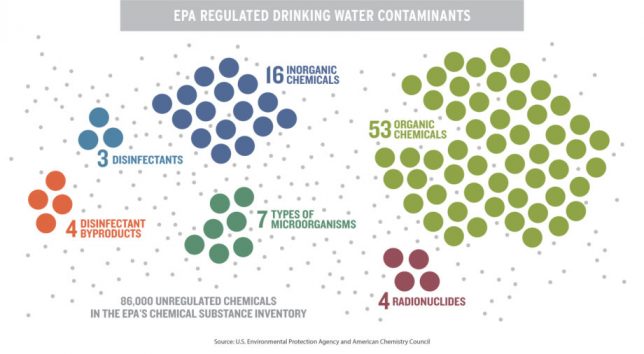

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) forms the foundation of federal oversight of public water systems — those that provide water to multiple homes or customers. Congress passed the landmark law in 1974 during a decade marked by accumulating evidence of cancer and other health damage caused by industrial chemicals that found their way into drinking water. The act authorized the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for the first time to set national standards for contaminants in drinking water. The EPA has since developed standards for 91 contaminants, a medley of undesirable intruders that range from arsenic and nitrate to lead, copper and volatile organic chemicals like benzene.

In 1996, amendments to the SDWA revised the process for developing drinking water standards, which limit the levels of specific contaminants. Nearly a quarter century after those amendments, an increasing number of policymakers and public health advocates today argue that the act is failing its mission to protect public health and is once again in need of major revision.

Setting Limits

The process for setting federal drinking water contaminant limits, which is overseen by the EPA, was not designed to be speedy.

First, the EPA identifies a list of several dozen unregulated chemical and microbial contaminants that might be harmful. Then water utilities, which are in charge of water quality monitoring, test their treated water to see what shows up. The identification and testing is done on a five-year cycle. The EPA examines those results and, for at least five contaminants, as required by the SDWA, it determines whether a regulation is needed.

Three factors go into the decision: Is the contaminant harmful? Is it widespread at high levels? Will a regulation meaningfully reduce health risks? If the answer is “Yes” to all three, then a national standard will be forthcoming. Altogether, the process can take a decade or more from start to finish.

Usually, however, one of the three answers is “No.” Since the 1996 amendments were passed, the EPA has not regulated any new contaminants through this process, though it has strengthened existing rules for arsenic, microbes and the chemical byproducts of drinking water disinfection. The agency did decide in 2011 that it should regulate perchlorate — which is used in explosives and rocket fuel and damages the thyroid — but reversed that decision in June 2020, claiming that the chemical is not widespread enough to warrant a national regulation.

Two other chemicals have recently advanced to the standard-writing stage. In February, EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler announced that the agency would regulate PFOA and PFOS, both members of the class of non-stick, flame-retarding chemicals known as PFAS. For those two chemicals, the EPA currently has issued a health advisory, which is a non-enforceable guideline.

The act of writing a national standard introduces more calculations: health risks, cost of treatment to remove the contaminant from water and availability of treatment technology. Considering these, the EPA establishes what is known as a maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG), which is the level at which no one is expected to become ill from the contaminant over a lifetime. The agency then sets a standard as close to the goal as possible, taking treatment cost into account.

Standards, in the end, are not purely based on health protection and sometimes are higher than the MCLG. These standards, except for lead, apply to water as it leaves the treatment plant or moves throughout the distribution system. They do not apply to water from a home faucet, which could be compromised by old plumbing.

The EPA also has 15 “secondary” standards that relate to how water tastes and smells. Unless mandated by a state, utilities are not required to meet these standards.

Once the EPA sets a drinking water standard, the nation’s roughly 50,000 community water systems — plus tens of thousands of schools, office buildings, gas stations and campgrounds that operate their own water systems — are obligated to test for the contaminant. If a regulated substance is found, system operators must treat the water so that contaminant concentrations fall below the standard.

Omissions and Nuances

That is the regulatory process at the federal level. But there are omissions and nuances.

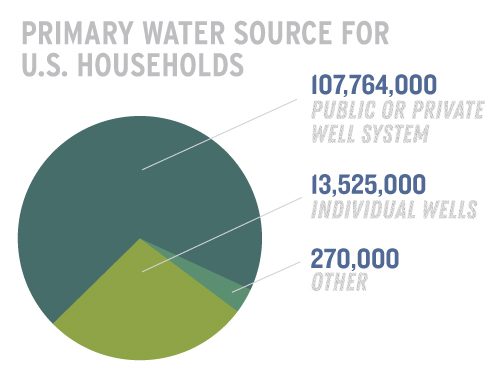

One big omission is private wells. Water in wells that supply individual homes is not regulated by federal statute. Rather, private well owners are responsible for testing and treating their own well water. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that about 15% of U.S. residents use a private well. Some states, such as New Jersey, require that private wells be tested for contaminants before a home is sold. County health departments might also have similar point-of-sale requirements.

The nuance comes at the state level. States generally carry out the day-to-day grunt work of gathering water quality data from utilities and enforcing action against violations. To gain this authority, they must set drinking water standards that are at least as protective as the federal ones. If they want, they can set stricter limits or regulate contaminants that the EPA has not touched.

State authority had long been uncontroversial because only a few states — California and some northeastern states — were setting their own standards. That has changed in the last few years as states, responding to public pressure in the absence of an EPA standard, began regulating PFAS compounds.

“There was always a little bit of state standards-setting,” says Alan Roberson, executive director of the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators, an umbrella group for state regulators. “But it’s gone from a little bit to a lot.”

Six states — Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York and Vermont — adopted drinking water standards for certain PFAS compounds, while four others, including North Carolina and Minnesota, have issued health advisories or guidelines for groundwater cleanup.

States are also putting limits on other chemicals that the EPA has ignored. In July, New York adopted the nation’s first drinking water standard for 1,4-dioxane, a synthetic chemical that was used before the 1990s as an additive to industrial solvents. The EPA deems it likely to cause cancer, but the agency has not regulated it in drinking water. In 2017, California approved a limit for 1,2,3-TCP, another manufactured industrial solvent that the EPA considers likely to be carcinogenic.

The burst of state standards, especially for PFAS chemicals, has raised eyebrows. Some lawmakers worry that mismatched standards are confusing to residents. New York and New Jersey, for instance, set different limits on PFOA and PFOS in drinking water.

“This can create poor risk communication and a crisis of confidence by the public who have diminished trust in their state’s standard when it fails to align with a neighboring state,” Rep. Paul Tonko of New York said during a House Energy and Commerce subcommittee hearing in July.

Other representatives countered with the view that the EPA should concentrate on a select number of the most concerning contaminants so as not to overwhelm utilities and states with too many rules that are too hastily put together. Rep. John Shimkus from Illinois, echoing statements made by other committee members, said he does not want a system in which “quantity makes quality.”

Tonko, however, argued that the federal process “has not worked,” pointing to the two-plus decades since a new contaminant was regulated.

This debate, and other considerations like regional drinking water standards, is likely to carry over into the next Congress.

Federal, state and local governments all have a hand in protecting public water systems and private wells from contamination.