By David L. Chandler, World Economic Forum (Public License).

- Coastal marsh plants provide significant protection from surges and devastating storms.

- Research in MIT’s Parson’s lab can help coastal planners to take important details into account when planning projects.

- Countries must take advantage of this modeling in order to restore marshland with specific plants in certain areas.

Marsh plants, which are ubiquitous along the world’s shorelines, can play a major role in mitigating the damage to coastlines as sea levels rise and storm surges increase. Now, a new MIT study provides greater detail about how these protective benefits work under real-world conditions shaped by waves and currents.

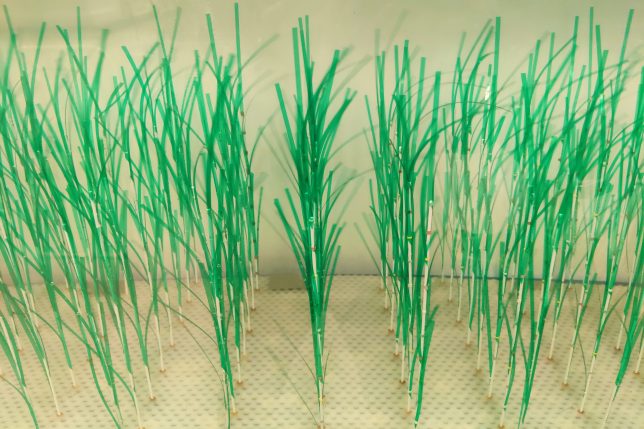

The study combined laboratory experiments using simulated plants in a large wave tank along with mathematical modeling. It appears in the journal Physical Review — Fluids, in a paper by former MIT visiting doctoral student Xiaoxia Zhang, now a postdoc at Dalian University of Technology, and professor of civil and environmental engineering Heidi Nepf.

“After a few years, the marsh grasses start to trap and hold the sediment, and the elevation gets higher and higher, which might keep up with sea level rise.”

—Xiaoxia Zhang, now a postdoc at Dalian University of Technology, and professor of civil and environmental engineering Heidi Nepf

It’s already clear that coastal marsh plants provide significant protection from surges and devastating storms. For example, it has been estimated that the damage caused by Hurricane Sandy was reduced by $625 million thanks to the damping of wave energy provided by extensive areas of marsh along the affected coasts. But the new MIT analysis incorporates details of plant morphology, such as the number and spacing of flexible leaves versus stiffer stems, and the complex interactions of currents and waves that may be coming from different directions.

This level of detail could enable coastal restoration planners to determine the area of marsh needed to mitigate expected amounts of storm surge or sea-level rise, and to decide which types of plants to introduce to maximize protection.

“When you go to a marsh, you often will see that the plants are arranged in zones,” says Nepf, who is the Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “Along the edge, you tend to have plants that are more flexible, because they are using their flexibility to reduce the wave forces they feel. In the next zone, the plants are a little more rigid and have a bit more leaves.”

As the zones progress, the plants become stiffer, leafier, and more effective at absorbing wave energy thanks to their greater leaf area. The new modeling done in this research, which incorporated work with simulated plants in the 24-meter-long wave tank at MIT’s Parsons Lab, can enable coastal planners to take these kinds of details into account when planning protection, mitigation, or restoration projects.

“If you put the stiffest plants at the edge, they might not survive, because they’re feeling very high wave forces. By describing why Mother Nature organizes plants in this way, we can hopefully design a more sustainable restoration,” Nepf says.

Once established, the marsh plants provide a positive feedback cycle that helps to not only stabilize but also build up these delicate coastal lands, Zhang says. “After a few years, the marsh grasses start to trap and hold the sediment, and the elevation gets higher and higher, which might keep up with sea level rise,” she says.

Awareness of the protective effects of marshland has been growing, Nepf says. For example, the Netherlands has been restoring lost marshland outside the dikes that surround much of the nation’s agricultural land, finding that the marsh can protect the dikes from erosion; the marsh and dikes work together much more effectively than the dikes alone at preventing flooding.

But most such efforts so far have been largely empirical, trial-and-error plans, Nepf says. Now, they could take advantage of this modeling to know just how much marshland with what types of plants would be needed to provide the desired level of protection.

It also provides a more quantitative way to estimate the value provided by marshes, she says. “It could allow you to more accurately say, ‘40 meters of marsh will reduce waves this much and therefore will reduce overtopping of your levee by this much.’ Someone could use that to say, ‘I’m going to save this much money over the next 10 years if I reduce flooding by maintaining this marsh.’ It might help generate some political motivation for restoration efforts.”

Nepf herself is already trying to get some of these findings included in coastal planning processes. She serves on a practitioner panel led by Chris Esposito of the Water Institute of the Gulf, which serves the storm-battered Louisiana coastline. “We’d like to get this work into the coatal simulations that are used for large-scale restoration and coastal planning,” she says.

“Understanding the wave damping process in real vegetation wetlands is of critical value, as it is needed in the assessment of the coastal defense value of these wetlands,” says Zhan Hu, an associate professor of marine sciences at Sun Yat-Sen University, who was not associated with this work. “The challenge, however, lies in the quantitative representation of the wave damping process, in which many factors are at play, such as plant flexibility, morphology, and coexisting currents.”

The new study, Hu says, “neatly combines experimental findings and analytical modeling to reveal the impact of each factor in the wave damping process. … Overall, this work is a solid step forward toward a more accurate assessment of wave damping capacity of real coastal wetlands, which is needed for science-based design and management of nature-based coastal protection.”

The work was partly supported by the National Science Foundation and the China Scholarship Council.