By Julie Mollins, Forests News (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Protecting and restoring landscapes and building sustainable agroforestry systems is a powerful way to boost resilience to climate change and extreme weather events while supporting billions of livelihoods.

Incorporated into the international framework on climate change in 2011 at COP17, adaptation became a specific area of focus at the U.N. COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, where a work program was established to define specific global goals pertaining to it.

At the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF), scientists are working on developing robust ecosystem-based adaptation strategies.

They must be part of broad, systems-wide approaches integrated into economic, political and social strategies, said Patrick Worms, senior science policy advisor at CIFOR-ICRAF, who led a side event discussion at COP26.

“The solution is thus not rocket science, but something much harder: the ability of our institutional systems to work across silos to jointly manage this fragile planet of ours.”

—Patrick Worms, senior science policy advisor at CIFOR-ICRAF

“We need to embed ecosystem adaptation – just like we need to embed mitigation – in the way the economy works, in the way government works, in the way that everything works, as we try to arrest carbon buildup, ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss,” Worms said.

Lalisa Duguma, a scientist in the CIFOR-ICRAF Sustainable Landscapes and Integrated Climate Actions team, is working on a large-scale ecosystem-based adaptation project, funded by the multi-billion-dollar Green Climate Fund (GCF) which aims to promote the climate-resilience of rural communities in Gambia.

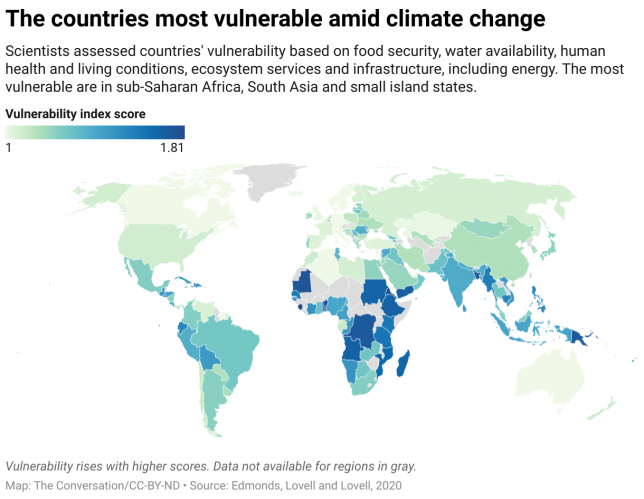

One difficulty working in African countries is that data on climate is scarce and inconsistent, which makes it a challenge to determine the extent of interventions required.

“Most is based on global data sets downscaled to the local context, but in this downscaling process, a lot of contextual realities are missing, which could inform the design process much better,” Duguma said.

Other challenges involve a lack of human resources and institutional capacity to implement adaptation actions, resource mismatches and how to measure the impact of interventions.

“In most ongoing adaptation actions, there is no clear strategy for scaling up – how scaling should go forward,” he said.

To address some of the challenges around capacity and infrastructure in Gambia, a baseline for tree cover was established, leading to investments into nine central nurseries and 100 million seedlings a year, said Malanding Jaiteh, who manages the $20 million, six-year forest restoration project on behalf of the country’s Ministry of Environment, Climate Change and Natural Resources.

Another challenge is livestock grazing which can compromise restoration efforts, making it difficult to plan and establish. Grazing is free range in Gambia, and even takes on an international dimension as nomadic herders at times enter the country from Senegal.

“Transmigration presents serious challenges, especially to our newly established seedlings or newly established planting areas — farmers may be planting in the agricultural lands, but as soon as they are gone, or two years later, you know, some other population can come in and start destroying them,” Jaiteh said.

Fires are also damaging and demand a lot of resources, requiring a long term fire management system, he said.

In India’s state of Maharashtra, where monocropping of cotton and sugarcane have left farmers vulnerable to climate change, a multi-jurisdictional and multi-sectoral approach is proving effective, said Arjuna Srinidhi, associate thematic lead of climate change adaptation at the Watershed Organization Trust.

More than 80 percent of the state consists of rainfed drylands, where drought frequency has increased sevenfold over the past 50 years, Srinidhi said. Flooding is also a problem and due to erratic weather, adding to the vulnerability of farmers. Over 40 percent of the land is degraded, and groundwater levels are falling rapidly by 1 to 2 meters every year. More than three quarters of the farmers are smallholders with less than 2 hectares of land, so their adaptive capacities are limited, he said.

Mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation strategies into government policies and programs is key, but we also learned that watershed development was vital.

“This collaborative process resulted in an evidence-based and demand-driven roadmap for upscaling,” Srinidhi said. “There were several lessons that we learned over the past couple of years, the unanimous acceptance of a roadmap from diverse stakeholders — generating a buy-in from early stages of the project was crucial.”

Serah Kiragu-Wissler, a research associate at TMG Think Tank for Sustainability, observed that capacity-building and extension services are essential. Farmers she worked with said they need ongoing support for adaptation efforts. Land tenure rights are also critical for soil protection, Kiragu-Wissler said, citing examples from Burkina Faso and Kenya.

“Farmers cannot develop much interest in protecting soils if they have no security to the tenure to the land that they are working on,” she said. “They clear their land this season they plant and next season they are not actually there. So, what will motivate them to carry loads of manure from the village to the fields if they cannot be assured that it will be there for you know, two, three, four seasons?”

By implementing a community-led institution for managing how land is used, guidelines were introduced which helped secure access to land for women and youth. Now recognized by the local government, this approach is under consideration by other jurisdictions, she said.

Finding finance

Ensuring adequate financing for ecosystem-based adaptation projects is also a challenge, particularly due to its innovative aspects and the fact that so many proposals are unproven.

“Banks, investors and insurance need to make better decisions by assessing the impacts and dependencies on nature and materiality around climate risks,” said Namita Vikas, managing director of auctusESG, a Mumbai-based financial advisory firm. “By deploying capital goods, and surveys, given the effectiveness of such solutions. Adaptation, finance is about going beyond business as usual and incorporating the possible effects of climate change into the design of an activity.”

Andreas Reumann, who works for the GCF, which was established under U.N. climate talks to help poor countries pursue clean growth and adapt to global warming, is a specialist in designing monitoring systems that measure for outcomes.

The fund conducted a global evidence review on adaptation and forest activities with partners, which helped reveal gaps in understanding what works in a specific context.

From there, a two-dimensional matrix was created, which illustrated an imbalance regarding the geographical distribution of information. It also highlighted the question of enabling environments – and how to engage the policy arena, which is a subject that has not yet been researched, Reumann said.

“We as evaluators are thinking about and addressing these issues,” he added. “It requires more knowledge sharing, stronger evidence, and more collaboration on the ground to truly understand what matters.”

Creating data sets has proven to be effective, said Nitin Pandit, director of the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment. By identifying 13 million hectares of land, with 100 million households, just outside the protected areas in peninsular India, and working with partners, accumulated data are supplied to financiers.

“So, they know that there is an upside in this because there is a scale that we are already planning in from day one,” Pandit said, sharing an image of large-scale elephants, which are made by artisans from lantana wood, an invasive species. Sold at a high price, the elephants were displayed outside Queen Elizabeth’s Buckingham Palace in London.

“The type of value addition that we can do by using the resources available must add an incentive for people to actually be engaged in adaptation, and therefore demand the kind of finance that is needed to support that kind of work,” he said.

For adaptation initiatives to be effective, it is vital to build dialogue processes and co-generate of the evidence base with government ministries, said Jessica Troni, senior programme officer responsible for the U.N. Environment Programme – Global Environment Facility Climate Change Adaptation portfolio. Budgets and systems thinking must be incorporated to determine how project targets can be mainstreamed into national development plans.

“Mainstreaming has to mean that every single chapter in your national development plan is geared towards building resilience to adaptation – you can then create budgets support for mechanisms that are able to absorb larger investment flows,” Troni said.

Promises to increase the coffers for adaptation ambitions were made at COP26 in an effort catch up with a shortfall in the $100 billion a year by 2020 pledged at COP17 amid efforts to avert, minimize and address loss and damage already occurring from climate change.

“The beautiful thing is that it’s extraordinarily hard to do land-based mitigation without, at the same time, boosting that land’s ability to adapt to climate change, its biodiversity or its ability to provide a range of nutritious foods and other products,” Worms said.

“The solution is thus not rocket science, but something much harder: the ability of our institutional systems to work across silos to jointly manage this fragile planet of ours.”