Colorado River as it meanders south towards the Grand Canyon, taken near to Horse Shoe Bend AZ. Source: herdiephoto, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Insights from a New Comprehensive Water Accounting Study

The Colorado River, a lifeline for over 40 million people and over two million hectares of cropland, barely trickles into the Gulf of California’s shores. The river has reached a critical juncture due to decades of overuse and climate challenges.

A new study published in Nature provides a comprehensive water budget, shedding light on the intricate dynamics of water consumption and offering a roadmap toward sustainable management. The river’s dwindling flows underscore a pressing need for strategic interventions to ensure its survival and continued support for millions of people and vast agricultural lands.

The Heart of the Matter

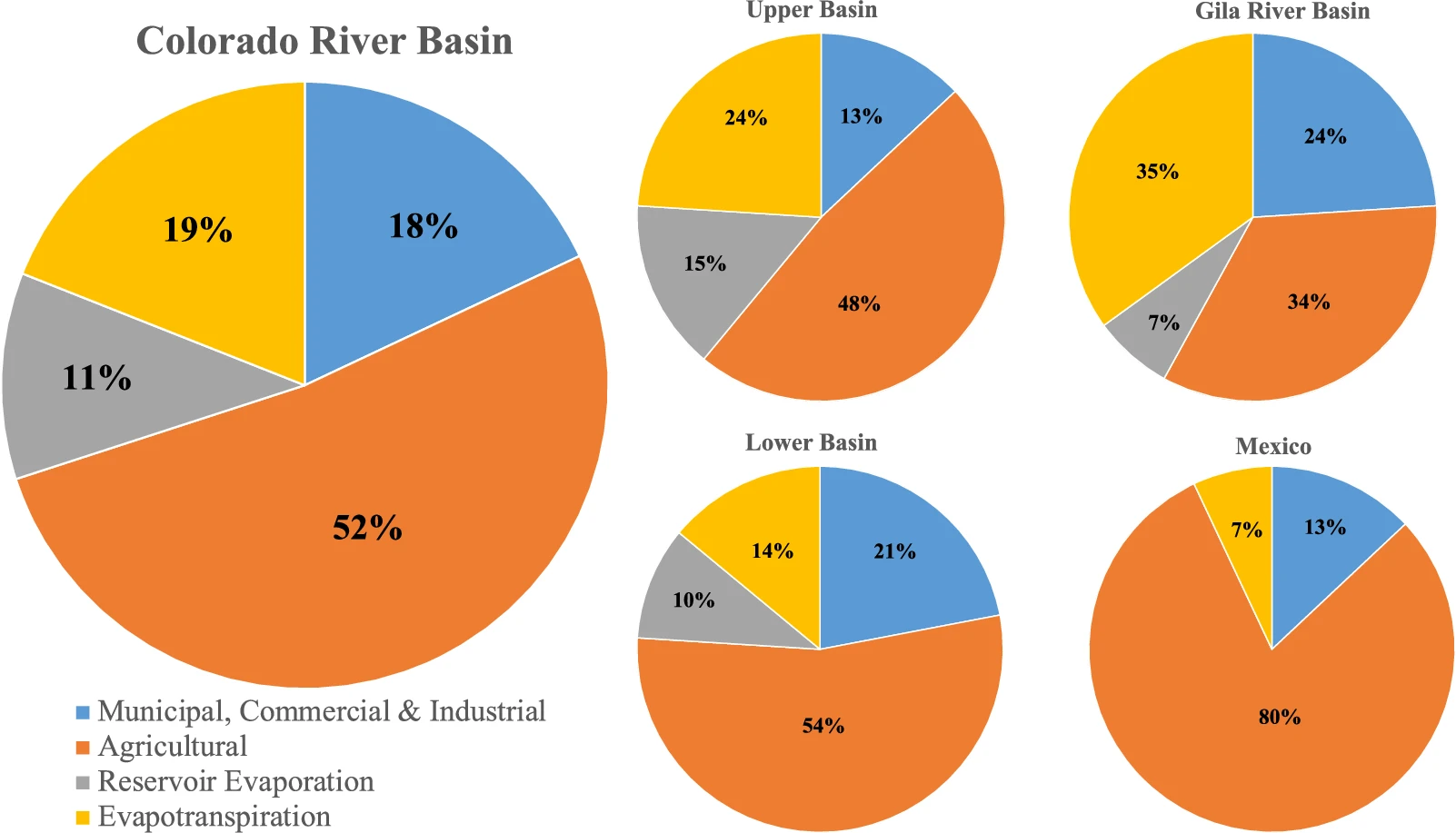

The multi-year study conducted between 2000 and 2019, provides a granular analysis of water usage patterns, pinpointing agriculture as the dominant consumer. The findings indicate that irrigated agriculture accounts for a staggering 74% of direct human water use, with cattle feed crops such as alfalfa and grass as significant water guzzlers, accounting for 46% of direct water consumption.

Water consumed by each sector in the Colorado River Basin and sub-basins (including exports), based on 2000–2019 averages from the study New water accounting reveals why the Colorado River no longer reaches the sea (Fig. 4).

The Colorado River’s Dilemma

The Colorado River’s plight tells a tale of natural variability alongside a stark reflection of human choices and their impacts on natural resources. The study’s revelations about the scale of agricultural water use, especially for cattle feed, invite a critical reassessment of water allocation priorities and the sustainability of current agricultural practices.

Navigating the Waters Ahead

Addressing the Colorado River’s challenges requires a multifaceted approach, combining policy reforms, technological innovations, and shifts in agricultural practices. The study advocates for a balanced water budget and the adoption of water-efficient technologies and crops.

With cattle feed crops utilizing a considerable portion of the river’s water, the study suggests reevaluating crop choices and water use efficiency. Implementing more sustainable practices, including alternative cropping patterns and enhanced irrigation techniques, could substantially reduce water stress. Moreover, it underscores the importance of collaborative water management strategies involving all stakeholders to ensure equitable and sustainable use.

Final Thoughts

The Colorado River’s diminishing flows serve as a wake-up call to address the unsustainable patterns of water consumption that threaten this critical water source. The comprehensive study lays the groundwork for informed decision-making, urging immediate action to safeguard the river’s future. Through collective efforts and sustainable practices, there is hope for restoring the balance and ensuring the Colorado River continues to sustain the Southwest for future generations.

Source: Richter, B.D., Lamsal, G., Marston, L. et al. New water accounting reveals why the Colorado River no longer reaches the sea. Commun Earth Environ 5, 134 (2024).