In Midland, Michigan, days of heavy rain caused two dams to fail forcing 10,000 people to evacuate. Midland is home to 42,000 people and the Dow Chemical Company’s main plant. If the flood water overtakes the plant’s

levees, experts worry hazardous chemicals could wash downstream. Coverage by Vice News.

Category: Pollution

Preventing Future Pandemics Requires Sweeping U.S. Action on Wildlife Trade

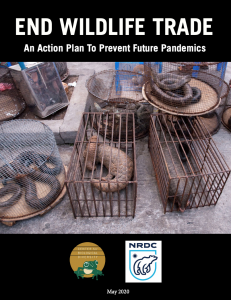

WASHINGTON— Conservation groups released a sweeping action plan today for the United States to dramatically crack down on wildlife trade, which is the most probable cause of the global coronavirus pandemic. Among other proposals, the action plan recommends that the United States end live wildlife imports, curtail all other wildlife trade until stricter regulations are adopted, and take a global leadership role in controlling wildlife trade to stop future pandemics.

Over the past 40 years, most global pandemics — including HIV, SARS, Ebola and Zika — have been zoonotic, meaning that they jumped from wildlife to people. The coronavirus likely originated from a live wildlife market in China — potentially passed from a bat, to another animal, to a human. Wildlife markets typically sell many different types of live wildlife, including both legally and illegally sourced animals.

“If we’re going to avoid future pandemics, the United States and every other nation needs to do its part to stop the exploitation of wildlife.

…“The loss of life and other devastating impacts of the coronavirus make it clear that the meager economic benefits of commodifying wildlife are simply not worth the risks.”

—Brett Hartl, Government Affairs Director at the Center for Biological Diversity

Irresponsible wildlife trade is a global problem. Importing more than 224 million live animals and 883 million other wildlife species every year, the United States is one of the world’s top wildlife importers. It also remains a common destination for illegally traded species. The United States and other nations have made only half-hearted efforts to address the impacts of wildlife trade and lack capacity to address trade effectively.

Today’s action plan, released by the Center for Biological Diversity and the NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council), proposes actions under four broader categories that Congress and federal agencies should implement to prevent future zoonotic pandemics:

- Lead a global crackdown on wildlife trade;

- Strengthen U.S. conservation laws to fight wildlife trade;

- Invest $10 billion in U.S. and global capacity to stop wildlife trade, while helping communities transition to alternative livelihoods; and

- Resume the U.S. position as a global leader in international wildlife conservation.

“This pandemic has made clear: wildlife trade is not only a threat to biodiversity—it’s also a threat to global public health.

…“China’s response to the COVID-19 crisis took quick action to restrict wildlife trade. In contrast, the U.S. has failed to take a single step towards minimizing this threat. That should change now.”

—Elly Pepper, deputy director for International Wildlife Conservation at the NRDC

Biodiversity loss, high rates of deforestation, and vast increases in agricultural development are leading to an increase in human encroachment into previously undisturbed habitat and contact with wildlife. As people move deeper into these last natural areas of the planet, scientists believe that infectious diseases will continue to emerge. Experts predict that new diseases will emerge from wildlife to infect humans somewhere between every four months and every three years.

###

The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, nonprofit conservation organization with more than 1.7 million members and online activists dedicated to the protection of endangered species and wild places.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is an international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 3 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City; Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Chicago; Bozeman, Montana; and Beijing.