A selection of gift ideas to show love for your people and your planet

By Daisy Simmons, Yale Climate Connections

‘Tis the season for conundrums — at least for the climate-conscious who find themselves torn between reducing carbon emissions and holiday gift-giving. So take heart: It IS possible to indulge in your generous nature while keeping a lighter carbon footprint.

Read on for three categories of climate-conscious gifts.

For those equally climate-virtuous

Some people on your list may be just as climate-conscious as you. As such they may be happiest with a present that’s climate-conscious and that combats emissions — whether through direct action or educating more people about the problem, and the solutions.

- The World Economic Forum has a few tips that might appeal to your recipients, such as planting a tree or buying a piece of coral in their name.

- Or consider a Climeworks gift certificate for direct-air carbon capture. The group says a $30 gift, for example, will remove and store 25 kg CO2 in your recipient’s name.

- Looking for an emissions-reducing gift for the whole household? Yale Climate Connections regular contributor Dana Nuccitelli suggests taking advantage of the tax credits and rebates available in the Inflation Reduction Act. “Now’s the time to upgrade your gas water heater or stove to a cleaner heat pump or induction version,” he says. “What better gift for your family than cleaner indoor air, plus lower monthly energy bills?”

- Want something a little more budget-friendly that also helps improve your home efficiency? Make a draft dodger snake — Bob Vila has some simple and cool DIY ideas here.

- Your fellow climate-oriented friends and family may also appreciate catching up on their related reading. For these folks, check out Michael Svoboda’s YCC review of 12 new titles for climate activists and academics.

- For those who prefer to learn through cinema, find out if the Wild and Scenic Film Festival On Tour is heading to your neck of the woods.

- For more emissions-busting gift tips, check out our 2021 gift guide for tips on Buy Nothing communities, climate action vouchers, and renewable energy credits.

Memorably material-free: Experiences and homemade treats

Material-free gifts like tickets to games or shows, babysitting vouchers, and memberships mean good times — and generally low to no planet-warming emissions compared with the impacts of producing and transporting material goods.

Here are a few for your giving inspiration:

- Got a kayaking enthusiast on your list? Turn to a local outfit for guided kayaking, snowshoeing, and other fun treks. Or head to Airbnb to scout for unique locally hosted experiences, from beginner surfing lessons in Santa Cruz to mountain e-bike touring in Asheville, North Carolina.

- Check out classes based on your recipients’ interests, like in-person cooking classes at a local co-op or kitchen store, a knitting class, or perhaps a belly-dancing class.

Quality online options are seemingly endless now, too, thanks to Masterclass (think intentional eating with author Michael Pollan or conservation with Jane Goodall) and Udemy (explore a range of courses on climate change plus hundreds of lessons in gardening, among many others.) - For your 21-plus set, book a tour to a carbon-neutral provider convenient to them. For example at the New Belgium brewery in Fort Collins, Colorado, your gift recipient can learn all about Fat Tire, America’s first certified carbon-neutral beer.

- Look into local museum and performing art center memberships for the culture-oriented people on your list. Or consider a subscription you know they’ll love, like New York Times Cooking ($5/month).

- Give the priceless gift of time in nature in the form of an America the Beautiful National Parks and Federal Recreational Lands Pass — an annual pass that gets one vehicle into any national park or forest ($80). Many states also offer annual state park passes: California, Florida, Maryland, and more.

- Got something you’re really good at? Offer up services for friends and family, like a bike repair, massage, oil change, or even tax prep.

There’s also still time to make something that wins over loved ones’ hearts … and appetites. You might whip up a batch of seasonal salted pecan caramel popcorn or glögg using organic ingredients and a reusable container.

Or, really please your crowd and take a cue from YCC contributor Karin Kirk’s holiday playbook. She gifts bread kits — “Put the dry ingredients for a no-knead bread in a silicone or plant-based/non-plastic bag, and send it off with instructions for mixing, rising, and baking. Instant treat.”

Her other holiday hit? “Boozey treats,” she says. “We’ve put our garden to proper use making plum gin and raspberry vodka. And honestly, it’s hard to go wrong with this theme!”

Material goods you can feel good about gifting

While other categories of gifts may be even more climate-friendly, a growing number of retailers are ramping up their own carbon neutrality efforts. Many shops are brimming with sustainable gift options, from solar gadgets to recycled jackets and shoes.

First, a few rules of thumb to help make any shopping expedition a little climate-friendlier:

- Consider who you’re buying FOR. Retail returns in 2021 accounted for 16.6 percent of total U.S. sales, according to the National Retail Federation. And with an “estimated 10 percent of all returns ending in a landfill, the environmental impact is not trivial,” per McKinsey analysis.

Avert returns with a gut check before making any purchase. Is your prospective gift something they need or want? And is there actually room for it in their home? Also consider asking about and honoring people’s wish lists. - Consider who you’re buying FROM. Some retailers are climate-friendlier than others — find out who they are and favor them in your shopping choices. Small, local businesses may be a good place to start. Also look for retailers with reputable, relevant certifications, like Climate Neutral, Corporation B, EWG-Verified, or 1% for the Planet.

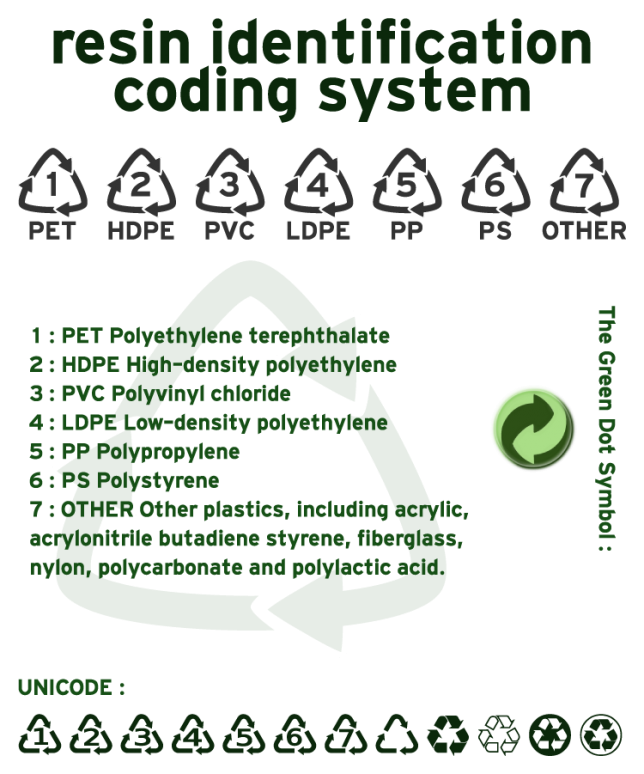

- Consider what materials are used. Look for renewable/reused/recycled materials wherever possible and avoid plastic gifts — unless they’re made with recycled or ocean-bound plastic. According to Beyond Plastics research, the U.S. plastics industry contributes roughly 232 million tons of CO2e gas emissions per year — equivalent to the average emissions from 116 coal-fired power plants. Plus, just under 9% of plastic in the U.S. is actually recycled, according to Environmental Protection Agency data.

Enough with the don’ts, let’s get to the do’s. Here are a few low-impact physical gifts for the recipient archetypes on your list:

The clean energy buffs

- EV owner in your life? Check out Clean Technica’s gift picks for Tesla drivers.

- Solar enthusiast? Consider a solar phone charger, solar backpack, or solar stove they can take camping.

The foodies

- Inspire their love of plant-based fare with a vegetable-centric cookbook. Food & Wine’s list has 16 contenders, from easy weeknight wins to James Beard-winning chef creations.

- Help them store their delectables with pretty beeswax food wraps, and then clean up the mess with biodegradable, reusable Swedish cloths.

- Food writers from a range of publications swear by the reBoard cutting board, made from recycled kitchen scraps.

- Score intrigue points with a novel — and climate-friendly ingredient — like kelp. Atlantic Sea Greens offers foodie fare like cranberry kelp cubes perfect for making smoothies, or try the Ginger Sesame Sea-Veggie Burger.

The musically minded

- Look for instruments with Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. Martin and DeMars are examples of companies prioritizing FSC-compliant renewable wood in their guitars.

- The House of Marley offers headphones and earbuds made with FSC-certified wood and recyclable aluminum — in addition to supporting global reforestation via One Tree Planted, and ocean conservation via the Surfrider Foundation.

The gardeners

- Gather an assortment of pollinator-friendly and heirloom seeds appropriate for your recipient’s zone and make a theme basket. Potential add-ins include biodegradable CowPots (Karin’s go-to) and a sturdy and sustainable hand tool.

- Splurge on a Haws watering can (also Karin-approved), handmade in England by a socially and environmentally responsible company that’s been around for 100+ years. These are hard to find in the U.S., but this Canadian retailer sells them and is Black-owned, certified B-Corp and donates 1% of profits to environmental projects.

- Another splurge? Borrow Dana’s plan for his mom (spoiler alert, Dana’s mom!) and gift a bird feeder with a camera powered by solar panels.

The ones who appreciate your keen fashion sense

- If you’re shopping for jewelry, opt for baubles made with recycled gold and silver, responsibly mined stones, and conflict-free diamonds. Treehugger has more tips here.

- For toiletries, head to Henry Rose Fragrance, billed as the first fine fragrance line to be both EWG Verified and Cradle to Cradle Certified; Good Time’s low-waste shampoo, conditioner and body soaps; and/or Carbon-Neutral-certified Leaf’s plastic-free razors.

- Need socks? A few climate-conscious contenders out there include Bare Kind’s Rainforest Trust bamboo socks made at a third-generation family-run factory and The Giving Socks, where every pair you buy supports tree restoration in Africa.

- For outerwear, check out Patagonia’s “recrafted” line of garments made from old clothes. Climate-neutral, B-certified TenTree also offers a wide range of stylish jackets and coats.

- Shoes offer a world of climate-conscious opportunity, from Thousand Fell’s fully recyclable sneakers and Cariuma’s National Geographic Gecko canvas shoes made with organic cotton, sustainably sourced rubber, cork and recycled plastics to Rothy’s ballet flats, knit from single-use plastics and available in 21 colors.

For the kids—and kids at heart

- From stackables to push cars, little ones love the sustainable wooden toys from PlanToys.

- For school-age kids, try plantable pencils they can use now, plant later.

- Your young Lorax lover will love the “I speak for the trees” hoodie at tentree.

- The rainforest-guardian doll, aka “Lottie,” is made with recycled cardboard, soy ink, and bio-degradable string — and a portion of your goes to the Rainforest Trust.

- Check out Eco-bricks for budding engineers. Any of these FSC-certified wood building sets is ready to please, but the Wanderlust collection’s architectural builds may especially delight kids who live in featured cities like Chicago.

- Help older kids learn about climate change — and action — with video games that bring climate issues front and center, like one of these.

Check the climate-conscious off your gift list

By thinking outside the gift box and exploring new ways to bring climate consciousness to gift-giving, you can unlock the next level of holiday spirit: to act generously and responsibly.