By Kimberley Brown, Mongabay (CC BY-ND 4.0).

QUITO, Ecuador — Indigenous communities across Ecuador celebrated over the weekend after a historic ruling by the country’s highest court declaring that Indigenous communities have more autonomy over their territory and a much stronger say over extractive projects affecting their lands.

“This has been a very big news, very important for the community, for all of us who have been on this path,” said Nixon Andy, from the Indigenous Kofan community of Sinangoe in Ecuador’s northern Amazon rainforest.

Ecuador’s Constitutional Court, the country’s highest court, made the ruling on Feb. 4 after reviewing Sinangoe’s 2018 lawsuit, in which the community sued three government ministries for selling mining concessions on their territory without consultation. Provincial judges at the time ruled in favor of the community and the rights of nature, overturning 52 mining concessions.

But last week, the Constitutional Court took this ruling one step further. After reviewing the evidence and traveling to Sinangoe to hold a historic hearing in Indigenous territory last November, the judges found there was a violation of a number of the community’s rights. This includes their right to be consulted before extractive projects are developed on their land.

As a result, the court ruled that the state has an obligation to ensure that communities undergo a consultation process before any extractive activity is planned on or near their territory. This process must also be “clear and accessible” for the whole community, and be carried out with the purpose of “obtaining consent or reaching an agreement with” the communities, according to the 39-page ruling.

Lina Maria Espinosa, a senior attorney with Amazon Frontlines, the environmental NGO that has been supporting Sinangoe, said the ruling will have an immediate impact on any oil or mining activity in any Indigenous territory in the country, as they must now undergo a consultation process with communities and obtain the community’s consent.

“The sentence seems to be an advance in the recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples to consent [to projects affecting their land], which is the ultimate purpose of the consultation,” Espinosa wrote to Mongabay in a text message.

“This goal must be pursued by the state ALWAYS,” she wrote.

Absent and faulty consultation process

According to Ecuador’s Constitution, Indigenous communities must be consulted before any oil, mining or other extractive projects begin on or near their territory. This is upheld internationally, under Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization, which guarantees Indigenous communities access to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC).

Despite these legal mechanisms, prior consultation has been a major point of conflict in the small South American nation. Many Indigenous communities say they were either never consulted before oil or mining projects were developed on their land, such as the community of Sinangoe, or that the process was faulty.

In 2019, Ecuador’s Waorani sued the state for conducting a flawed consultation process with the community in 2012, which they said was based on lies, misinformation, and a lack of translation necessary for elders who don’t speak Spanish. The court ruled in favor of the community, calling the process fraudulent. This ruling put into doubt all other consultations the government had conducted with communities across the Amazon in 2012, a process that led to the division of the rainforest into oil blocks to be sold to international investors.

Andres Tapia, communications director with Ecuador’s Amazon Indigenous federation, CONFENIAE, said the consultation process had been reduced to an “administrative process.”

“They complied with the requirement to say that [communities] had been consulted, when in reality there was no real relevant consultation process,” Tapia told Mongabay.

The Constitutional Court’s ruling is “historic,” Tapia said, as it “provides a guideline for the right to consent, whereby the community has the final decision on whether or not to allow any extractive activity,” he added.

President Guillermo Lasso has not yet commented on the ruling, as he is currently in China trying to renegotiate his country’s massive debt with Beijing. The ruling could hamper his administration’s plans to double both oil and mining across the country, in order to address Ecuador’s economic crisis that has seen unemployment and poverty spike during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oil and mining account for a combined more than 8% of Ecuador’s GDP.

The Constitutional Court ruling leaves the door open for the government to advance with certain extractive projects without consent from the community in “exceptional circumstances.” But, it stipulates, these initiatives can never “generate disproportionate sacrifice to the collective rights of communities and nature.”

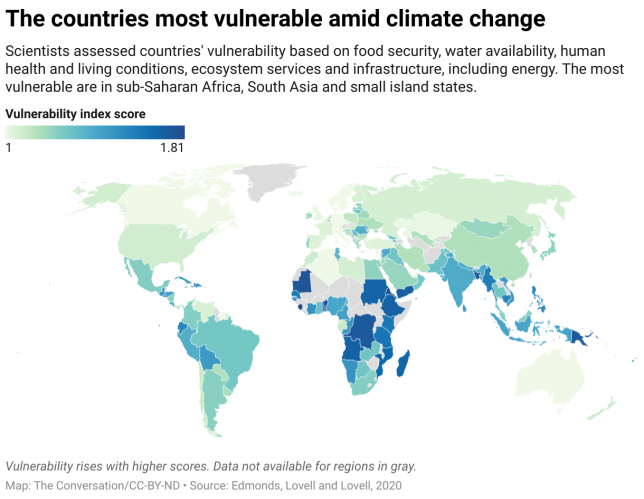

There are 14 Indigenous nations in Ecuador, many of them living in areas rich in oil and mineral deposits. This is particularly true in the Ecuadoran Amazon, where the vast majority of the country’s crude oil reserves are located. At the same time, 70% of the region is also designated Indigenous territory, CONFENIAE said. Scientists also say that an intact Amazon is essential to tackling climate change.

Of the nine Constitutional Court judges hearing the recent case, five ruled in favor of this final ruling, three ruled against, and one abstained.

“The Constitutional Court ratified that the state has to listen to us, so this sets a very important precedent for us, and for the whole Indigenous world, because our voices are not always listened to,” Andy told Mongabay.