Impact Characterization of Biodegradable Plastics

Credit: Piao, Z., Boakye, A. A. A., & Yao, Y. (2024). Environmental impacts of biodegradable microplastics. Nature Chemical Engineering, 1, 661–669.

When you hear the word “biodegradable,” what comes to mind? Many of us assume biodegradable plastics are a perfect solution for reducing plastic pollution. However, these materials have complex environmental impacts that aren’t immediately obvious. While they can help reduce certain types of pollution, they also come with hidden trade-offs, including greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

In this article, we’ll dive into the environmental impacts of biodegradable plastics, explain how Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) helps scientists understand their effects, and offer tips for more eco-friendly choices.

What Are Biodegradable Plastics?

Biodegradable plastics are materials designed to break down in the environment faster than traditional plastics. They are typically made from renewable resources, like corn starch or sugarcane, or from fossil-based sources. Common types include plant-based PLA (polylactic acid) and fossil-based PCL (polycaprolactone).

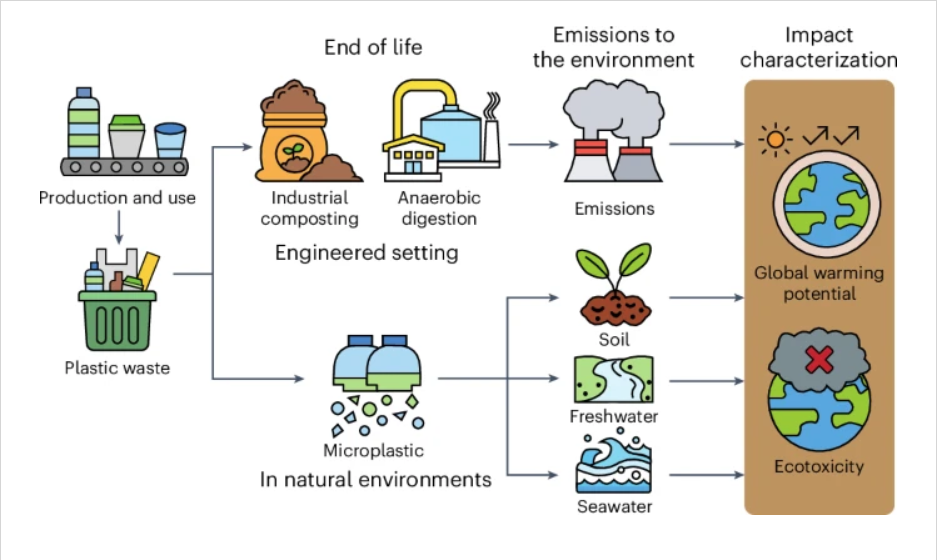

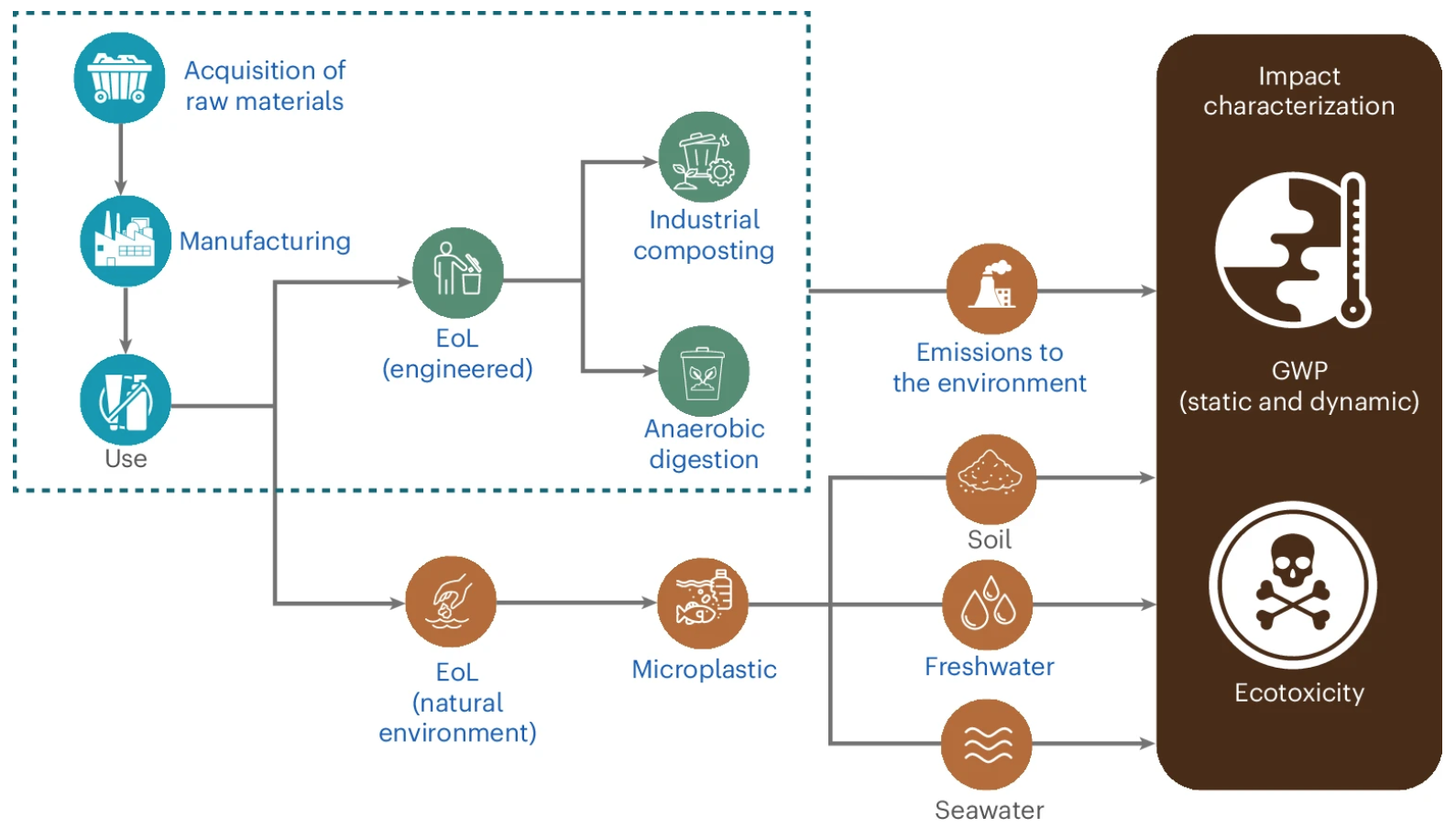

To fully understand their impact, scientists use a process called Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA). LCIA evaluates a product’s environmental footprint across its entire life cycle—from production to disposal. This is essential for understanding biodegradable plastics’ real impact on our planet, including factors like greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, and waste management challenges.

Benefits of Biodegradable Plastics in Reducing Microplastic Pollution

One of the most significant benefits of biodegradable plastics is their potential to reduce microplastic pollution. Microplastics are tiny plastic fragments that pollute our oceans, rivers, and even our food and water. Because they don’t easily decompose, they accumulate in ecosystems and can harm wildlife and human health.

Biodegradable plastics offer a promising alternative. When they break down properly, they are less likely to form these harmful microplastics. Scientists assess this potential benefit through a measure in LCIA called aquatic ecotoxicity, which looks at how materials impact aquatic life. Biodegradable plastics typically score lower in aquatic ecotoxicity than traditional plastics because they break down more completely, reducing the risk of long-term pollution.

Think of biodegradable plastics like “biodegradable litter.” If disposed of properly, they disappear without leaving a trace, unlike conventional plastics that break into microplastics and linger in the environment for years.

Impact Characterization of Biodegradable Plastics

Credit: Piao, Z., Boakye, A. A. A., & Yao, Y. (2024). Environmental impacts of biodegradable microplastics. Nature Chemical Engineering, 1, 661–669, Figure 1.

Hidden Costs of Biodegradable Plastics: Greenhouse Gas Emissions

While biodegradable plastics can reduce visible pollution, they aren’t without environmental costs. As these plastics break down, particularly in natural environments like rivers or forests, they can release greenhouse gases (GHGs) like methane—a potent contributor to climate change.

Here’s a surprising statistic: when PCL, a common biodegradable plastic, breaks down in a natural setting, it can emit up to 16.3 kilograms of CO₂-equivalent per kilogram of plastic. This emission rate is about 16 times higher than what it would release in an industrial composting facility.

Scientists use Global Warming Potential (GWP) within LCIA to measure how much a material contributes to climate change. For biodegradable plastics, scientists often use dynamic GWP calculations, which track greenhouse gas emissions over time rather than assuming a constant rate. This approach reveals that biodegradable plastics can emit GHGs in bursts as they break down, especially under anaerobic (low-oxygen) conditions in natural environments.

In some scenarios, biodegradable plastics that aren’t properly managed may actually emit more greenhouse gases than traditional plastics.

Role of Waste Management in Reducing Environmental Impact

The environmental impact of biodegradable plastics depends heavily on how they are disposed of. Ideally, they should be processed in industrial composting facilities, where conditions like temperature and oxygen are carefully controlled to allow these plastics to break down quickly and with minimal greenhouse gas emissions.

However, when biodegradable plastics end up in natural environments, such as lakes or soil, they break down under uncontrolled conditions, leading to increased emissions.

Think of biodegradable plastics as “biodegradable litter.” Just as litter remains litter if tossed on the ground, biodegradable plastics can still pollute if not disposed of correctly.

This brings us to the End-of-Life (EoL) Impact stage in LCIA. LCIA considers the full “end-of-life” cycle of a product to evaluate its environmental footprint based on where it ends up. Without the proper disposal infrastructure, biodegradable plastics may add to environmental pollution rather than reduce it.

What the Future Holds for Biodegradable Plastics

As scientists learn more about the impacts of biodegradable plastics, they’re working to design materials that minimize environmental costs. Using tools like LCIA, researchers can adjust physical properties—such as density, degradation rates, and carbon content—so that biodegradable plastics break down with lower greenhouse gas emissions and reduced aquatic toxicity.

LCIA helps scientists make informed design choices that balance eco-friendliness with practicality. For instance, certain plastics might be designed with an optimized Specific Surface Degradation Rate (SSDR), which controls the rate at which they break down in nature. This helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions while ensuring the plastic still decomposes efficiently.

Think of it like a “recipe” for future plastics. Each ingredient—density, degradation rate, carbon content—needs to be carefully balanced to create a plastic that’s both sustainable and functional. Just as a recipe requires precision for the best result, so does the design of biodegradable plastics.

With LCIA as a guide, scientists and manufacturers can develop low-carbon biodegradable plastics that help protect the planet by reducing pollution and managing emissions.

What Can We Do to Make a Difference?

As consumers, we have a role to play in reducing plastic pollution and supporting sustainable materials. Here are some ways we can contribute:

- Mindful Consumption: Choose products with minimal packaging and support companies that use sustainable materials.

- Proper Disposal: Make sure biodegradable plastics go into the correct waste streams. Check local composting and recycling guidelines to see if your area has facilities for biodegradable plastics.

- Spread the Word: Share this information with friends and family. Understanding the pros and cons of biodegradable plastics helps everyone make more informed, eco-friendly choices.

Summing Up

Biodegradable plastics are a promising step toward reducing plastic pollution, but they also come with their own environmental costs, especially when they end up in natural environments. Through Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA), scientists help us understand these trade-offs, from reducing microplastic pollution to the hidden impacts of greenhouse gas emissions.

Ultimately, while biodegradable plastics offer benefits, they are only part of the solution. Proper disposal methods, innovative material design, and mindful consumer choices are essential to building a sustainable future for our planet.

Source: Piao, Z., Boakye, A. A. A., & Yao, Y. (2024). Environmental impacts of biodegradable microplastics. Nature Chemical Engineering, 1, 661–669. https://www.nature.com/articles/s44286-024-00127-0?error=cookies_not_supported&code=8b06b2c3-71e3-42e5-8edc-f9124ebb3fec