By Johnny Wood, Senior Writer, Formative Content, World Economic Forum (Public License)

- July temperatures in 2016, 2019, and 2020 were the hottest ever.

- The last fully intact ice shelf in Canadian Arctic collapsed in July’s heatwave.

- Climate change could double the area of central Europe affected by severe drought by the second half of the century.

The July just gone was the third-hottest ever recorded, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service. This isn’t the result of a one-off heatwave or freak weather front, but part of an alarming trend that has seen three of the hottest July months ever recorded – peaking in 2016, followed by 2019 – occurring within the past five years.

Have you read?

- A climate scientist explains what the melting Arctic means for the world

- The shrinking Arctic ice protects us all. It’s time to act

- 2020 is predicted to be the hottest year on record, according to NASA

June 2020 saw the joint-hottest average temperatures for this month, together with 2019. Both Junes had average global temperatures 0.5C above the 1981-2010 average.

For more temperate parts of the world, hotter summers are concerning. But what happens when summers get hotter in already very hot places?

Too hot to survive without air conditioning

This summer, Iraq’s capital Baghdad has endured some of the hottest days ever, with temperatures in excess of 50C, during a heatwave that has hit much of the Middle East. While the region is used to hot weather, countries including Israel and Lebanon have experienced unusual heat extremes, a sign of things to come as climate change continues to heat up the planet.

Humans could face a future that’s too hot to survive without air conditioning. Exposure to extreme heat can stress the body to the point where organs shut down, presenting potentially life threatening conditions for many people living in developing countries.

But hot weather is only part of the climate crisis story.

Warming temperatures make extreme weather events, such as floods, storms and droughts, both more likely and potentially more intense.

Warming temperatures could make extreme droughts as much as seven times more likely, according to new research. This means the area of cropland affected by extreme drought across central Europe could double in the second half of this century, to more than 40 million hectares (approximately 400,000 square kilometres), the Guardian reported.

Using precipitation and temperature data from records from as far back as 1766 to inform climate change computer models, researchers from the UFZ-Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in the German city of Leipzig forecast that moderate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions could reduce the drought-affected area of central Europe by 40%.

Sinking islands

In the icy wilds of remote northern Canada, the threat of droughts isn’t a consideration, but the region is no less affected by climate change.

At the periphery of Ellesmere Island sits the Milne Ice Shelf, the last fully intact ice shelf in the Canadian Arctic. July’s extreme heat caused two-fifths of this natural wonder to break up in just two days.

“This was the largest remaining intact ice shelf, and it’s disintegrated, basically,” Luke Copland, glaciologist at Canada’s University of Ottawa, told Reuters, explaining that summer temperatures in the Canadian Arctic this year climbed 5C above the 30-year average.

“You feel like you’re on a sinking island chasing these features, and these are large features. It’s not as if it’s a little tiny patch of ice you find in your garden.”

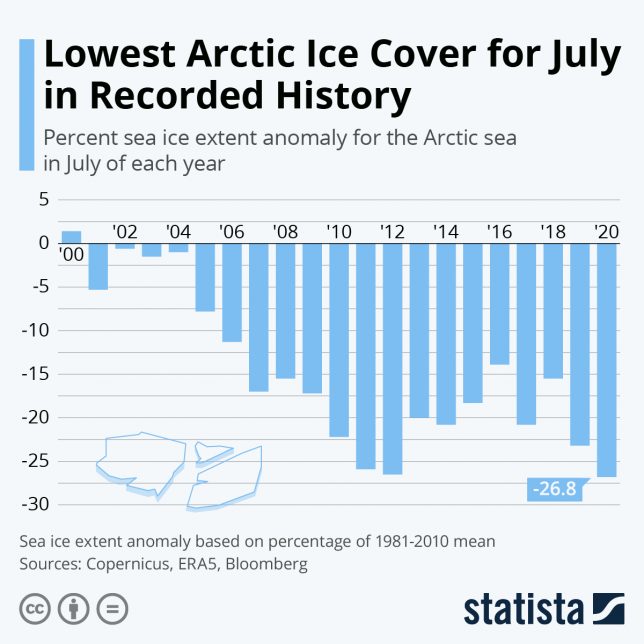

Extreme July temperatures have hit the entire Arctic region, which scientists say is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the planet. The 2020 summer melt produced the lowest recorded ice cover for the month of July since records began in 1981.

While the impact of global warming is clear to see, it’s not too late to curb emissions and tackle the climate crisis, but urgent action is needed to accelerate the journey toward net-zero emissions.